By Loren Yager and Martin Alteriis, US Government Accountability Office’s Center for Audit Excellence

Introduction

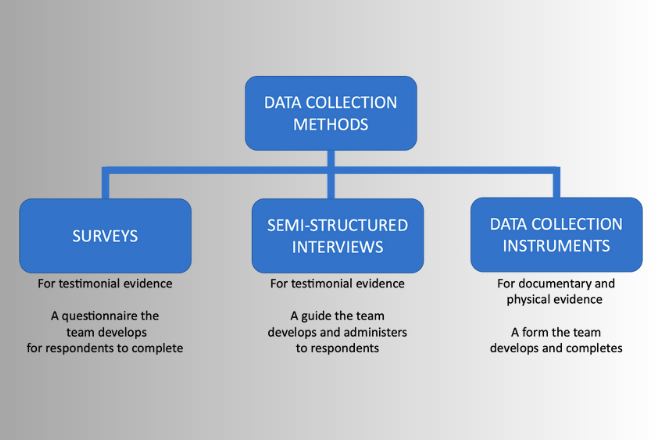

One of the distinguishing features of audit organizations and reports is the emphasis on evidence to support findings and recommendations, so any techniques that have the potential to make that evidence more powerful should be given high priority. One way that offers that potential is to closely examine three of the techniques used by audit organizations to collect evidence: surveys, semi-structured interviews, and data collection instruments (DCIs).

Surveys are an invaluable tool for audit organizations when the necessary information is not available from documentary sources, although the time and resources required to implement surveys limits their use. On the other hand, it appears that a better understanding of semi-structured interviews and data collection instruments has the potential to add rigor to audits without such a large investment. For example, audit organizations generally use some form of interviews in all their audits, and modest changes that add structure to the process may have a large payoff without much additional investment. Similarly, many audits involve inspections of some form, whether those are inspections of physical facilities or of agency documents. Using a more structured approach such as a DCI may also add power to the findings without added time or resources.

Figure 1: Types of commonly-used data collection methods

Surveys

Surveys can be an effective tool in the collection of audit evidence, particularly when there are no other ways to generate that type of information. For example, surveys are often the only way to collect information regarding opinions of respondents, and more generally, surveys offer a way to collect testimonial evidence in a more rigorous manner. In a sense, surveys offer an opportunity to make ‘data’ out of testimonial evidence.

The downside is that surveys that are of sufficiently high quality to serve as audit evidence are costly and time consuming to develop and implement. One of the crucial distinctions between surveys and the other two collection methods is that the audit team is not present when the respondents complete the survey. In contrast, semi-structured interviews and data collection instruments are administered or completed by members of the audit team (see figure 1). This distinction has implications for the time required for the preparation and pre-testing required for a survey. Since the team will not be present to address any questions, survey questions must be designed and implemented in a way that does not introduce bias or confusion and generates an acceptable response rate.

Figure 2 provides an illustration of the steps that are required to successfully complete a survey, although the time involved can vary greatly depending on factors such as the size experience of the audit team, the complexity and sensitivity of the subject matter, and the and the size and accessibility of the target population.

Figure 2: Key steps involved in survey implementation

There are cases where surveys are the best method available to collect evidence required for an audit, but as with any decision that involves a large investment, the use of surveys merits a careful examination of the costs and benefits of this technique vs. other methods of collecting audit evidence.

Semi-Structured Interviews

On the other hand, there are other data collection techniques that appear to have significant potential to add rigor without much additional investment. One of these can be called ‘semi-structured’ interviews, and these different from normal interviews as they often involve some combination of open-ended questions and closed-ended questions. The closed ended questions have a specified set of options for the responses, which could include yes/no, extent ranges (great extent, moderate extent, little extent), etc.

Semi-structured interviews have the potential to add rigor to the evidence collection process, as teams can use some of the same selection and implementation techniques as are used in surveys. The result is that additional time is needed in the development stage of the interviews since the goal is to have a more stable instrument before the interviews begin.

Figure 3: Adding structure to interviews shifts time to development

On the other hand, this advance planning has two potential benefits for the audit. One is that the planning of the interview tends to decrease the amount of time need in the later stages of the audit, particularly in terms of the analysis and documentation. For example, if the team has incorporated some closed ended questions in the interview, such as the example below, the range of responses is limited.

Did the training provide you with the skills necessary to carry out the inspections?

a. to a great extent

b. to a moderate extent

c. to a small extent

In those cases, the analysis and the documentation of the structured questions is greatly simplified since it only involves a tally of the responses. The semi-structured format is also flexible since the team can incorporate open-ended questions where the responses are not as easy to anticipate and categorize in advance.

A more important advantage of semi-structured interviews is that they have the potential to generate more powerful evidence and audit findings. For example, if the above question was one that was not part of a semi-structured interview, the key finding might read something like the statement on the left of figure 4:

Figure 4: Typical findings of unstructured vs. semi-structured interviews

On the other hand, if the same question was asked of all the respondents in the same manner, the audit team could report the evidence in a much more precise and powerful manner, as in the statement on the right-hand side of the Figure. Additional questions in a semi-structured interview could solicit additional insights on what aspects of the training were inadequate, so the semi-structured interview format provides a ‘best of both worlds’ approach for a modest investment in the development stage prior to the interviews.

Data Collection Instruments (also known as Analyst Data Entry Forms)

The second technique that can generate more powerful findings is the use of a DCI. These are structured data entry forms that analysts administer following procedures and processes developed for the audit. Many audit organizations likely employ these tools in one way or another, but the opportunity to add rigor to audits through these tools seems almost unlimited. One of the most common images of a data collection instrument is a building inspector with a clipboard checking off each of the required elements, although it may be more common now for the clipboard to be replaced by an electronic tablet of some kind.

This form of data collection instrument may be of value to auditors when they perform inspections of buildings, inventories, or other physical assets, and helps ensure that a consistent examination is applied to all the cases selected for review. However, data collection instruments may also be used to add rigor to the examination of documents provided by a ministry or department. For example, auditors frequently review progress reports or contracts to ensure that specific legal requirements are met, and it is often possible to create a data collection tool that enables auditors to perform a more consistent examination of the documents. As in the case of semi-structured interviews, there is a tradeoff between additional time in the development stage in return for easier analysis and more powerful results.

As an example, the text on the left is typical of the findings if the review is not conducted in a structured manner. By contrast, if a data collection instrument is utilized and auditors can categorize the quality of documentation into the three categories, the findings could be summarized in a graphic on the right with significantly greater impact.

Figure 5: Typical findings of unstructured reviews vs. use of a data collection instrument (DCI)

One of the additional advantages of the audit team’s development of a data collection instrument is that any steps taken to increase the rigor of evaluation is likely to pay off in other ways. For example, the team would have to clarify exactly what language is required based on the criteria such as the specific conditions that would merit a designation of ‘partial documentation’ vs. ‘complete documentation’. These rules would help ensure consistent application of the criteria and facilitate internal review prior to publication. This kind of rigor would be especially valuable when the auditee takes issue with the findings and asks to see the methodology. Without a rigorous set of decision rules and clear tally of results, the auditee might call for changes to the findings, but with a data collection instrument and clear decision rules, the audit team might even welcome a challenge to the methodology and the findings.

Conclusion

A key element of the ISSAI definition of Performance Auditing is “providing an independent and authoritative view or conclusion based on audit evidence.” As a result, any steps that government auditors can take that deliver more powerful evidence should be a high priority of audit organizations. Based on our experience with U.S. and international audit organizations, it appears that a more targeted use of surveys and more frequent use of semi-structured interviews and data collection instruments have the potential to power up audit evidence and maximize the positive impact of audit organizations.