IT-based Audits: A Powerful Tool in a Changing Audit Environment

by LEE Sooyeon, Director General, Bureau of Information Management; KIM Taeick, Director, and LEE Choongjae, Auditor, Division of Data Analysis and Information Management; SAI Korea

A Digital Transformation in Auditing

To better serve the needs of citizens and enhance services, many countries have introduced innovative e-government systems using information technology (IT). According to the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs’ (UN DESA) E-Government Survey 2020, most countries and municipalities are pursuing digital government strategies.

In Korea, which the UN DESA survey found to be among the leaders in e-government, many areas of public administration—such as health care, taxation, education, transportation, and land management—are conducted electronically, which has led to the exchange of digitized information among ministries. The government is also in the process of integrating emerging technologies (including artificial intelligence, data analytics, and 5G) into its e-government system to more effectively deliver services.

These changes in public administration in Korea and many other countries have led to a digital transformation in auditing. Auditors are increasingly supplementing, or even replacing, the traditional method of obtaining evidence—checking information in written documents—with one that centers on examining data stored in information systems. These IT-based remote audits can enhance efficiency, as auditors may not need to engage in the time-consuming, labor-intensive process of visiting every site in-person in order to examine auditees’ records. The disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic have only accelerated the shift to remote audits, as Supreme Audit Institutions (SAIs) work to bolster their resilience in challenging conditions.

An Effective System for Analyzing Digital Data

The Board of Audit and Inspection (BAI)—the SAI of Korea—continuously seeks to strengthen its efforts to gauge whether auditees adhere to regulations and operate in accordance with the principles of economy, efficiency, and effectiveness. To that end, BAI established BARON (Best Audit & Inspection System for Rule-based Observation Network) in February 2018 as a tool for collecting, sorting, and analyzing digital data.

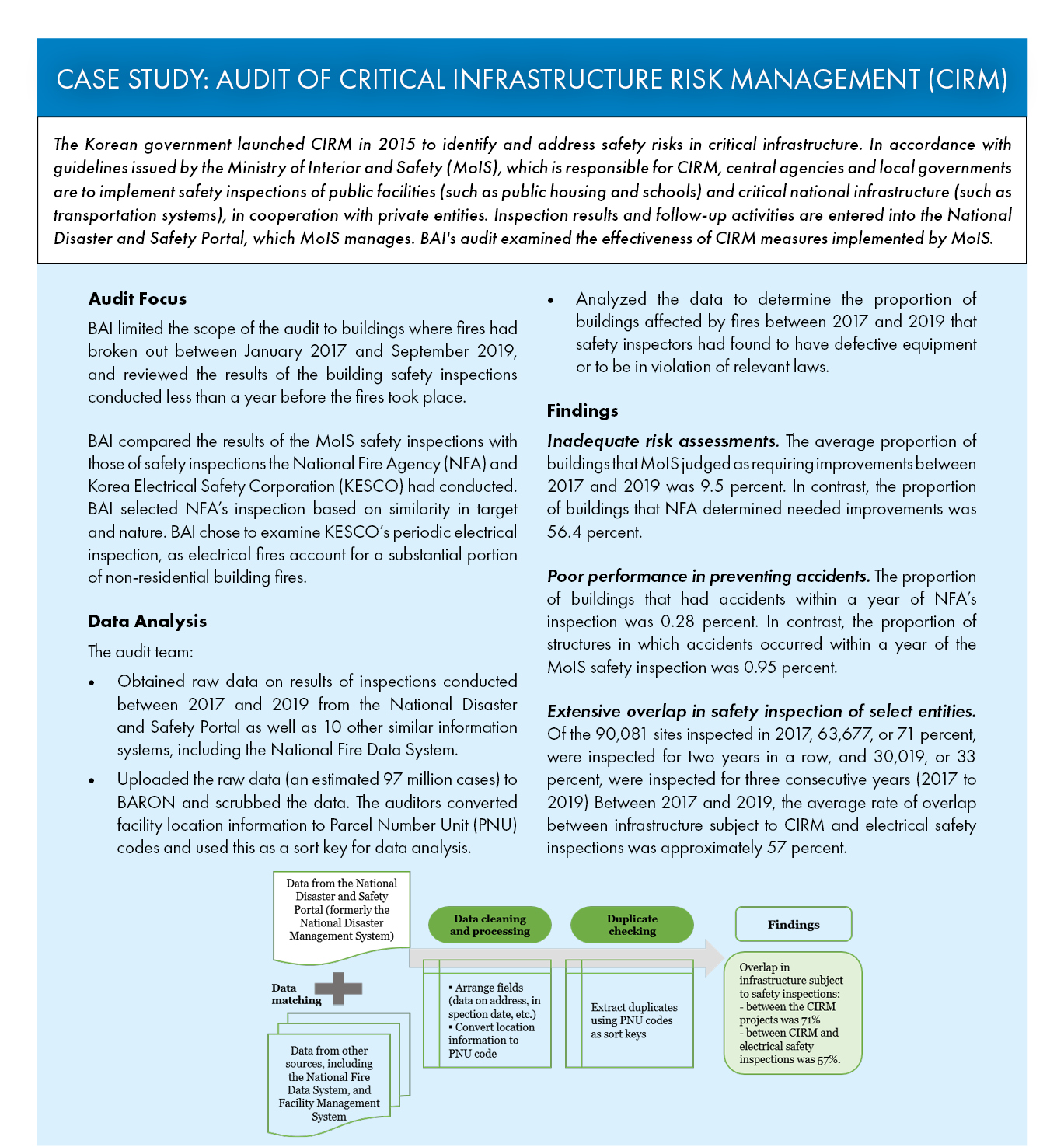

Collecting Data. Auditors frequently use public data related to specific areas (such as fiscal expenditures and contracts). BARON collects the data in line with the needs of auditors on a regular (monthly or quarterly) basis, processes the data into 653 different types for audit purposes, and stores the data. (See figure 1.)

While BARON made different kinds of data from various government entities more accessible, auditors could not initially access all the data they needed. To resolve this issue, BAI linked BARON to the data stored in the government’s metadata management system, which comprises 2,921 information systems and 451,200 databases. This improvement enabled auditors to search the list of digital data by organization, and to request that auditees submit to the SAI any data not retrievable from the system.

Sorting Data. Fiscal expenditure data is often classified into three groups based on whether they are related to projects of public institutions, infrastructure and maintenance, or government employment and social services, allowing auditors to locate and retrieve data with ease. Auditors can also use BARON to sort fiscal data by entering different sort keys according to their needs. Auditors can organize fiscal data related to public institutions’ projects by code number (e.g., government project codes for the year concerned, codes for financial institutions, etc.). BARON uses address as a sort key for data on government infrastructure expenditures, and personally identifiable information (PII) as a sort key for information on employment and social services.

Analyzing Data. In the early stages of BARON’s implementation, the system automatically identified possible irregularities in state or local finances from its accrued data. Auditors then examined whether any suspicious activities had occurred in the audited entities and provided recommendations for remediation. However, not all data were accessible through the system.

Today, BARON enables auditors to analyze financial data alongside other forms of data (such as vehicle registration details and geospatial data) from various sources. BAI created a spreadsheet tool in BARON that enables auditors to arrange data (such as date, address, and serial number) in a uniform format, analyze it (such as by extracting relevant data based on specific criteria), and compare values within or across datasets.

BARON also allows auditors to conduct spatial analysis—such as buffering (identifying a surrounding area within a specific distance of a geographic feature, such as areas affected by smoke from a building fire), overlay (superimposing information from multiple data layers, such as identifying areas that cover drinking-water protection zones and greenbelt land), and distance measurement—directly on a map.

BAI plans to continue to enhance the types of data analysis auditors can conduct in BARON. This could lead to more advanced IT-based audits, in which auditors use cutting-edge tools like Artificial Intelligence to analyze data.

Prospects and Challenges of IT-based Audits

In addition to developing BARON, BAI has made many efforts to encourage the use of IT-based audits, including establishing a dedicated Division of Data Analysis and Information Management (DDAIM). This division, together with the Audit and Inspection Research Institute (AIRI), provides support to audit divisions in collecting and analyzing digital data and evaluates BARON’s performance in order to improve the system. BAI also promotes IT-based audits by selecting and awarding exemplary IT-based audit cases biannually.

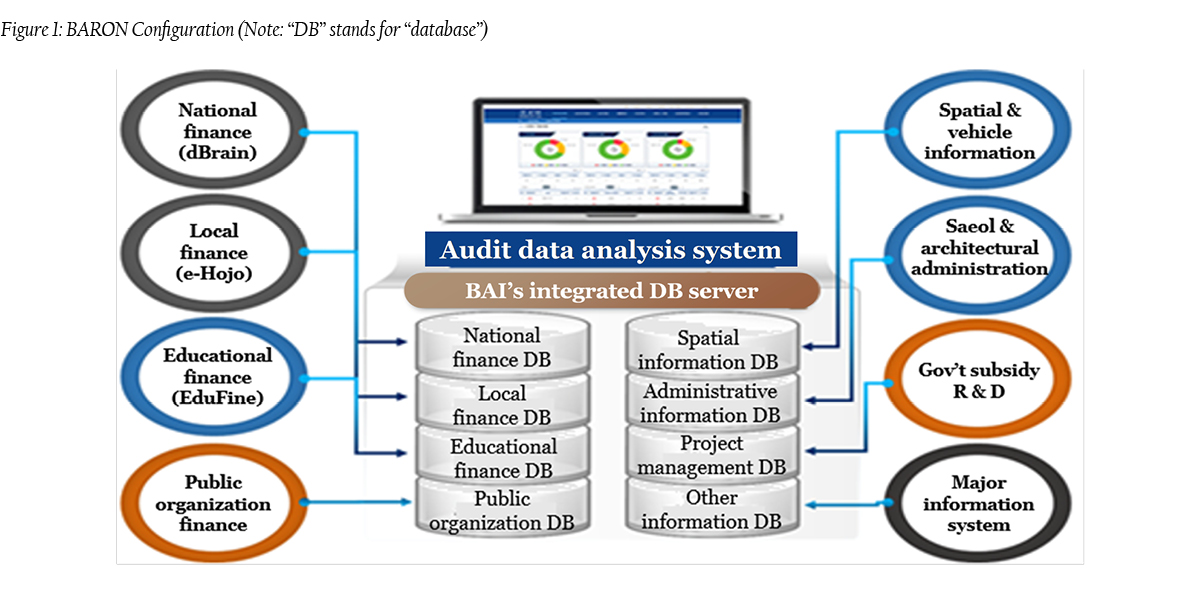

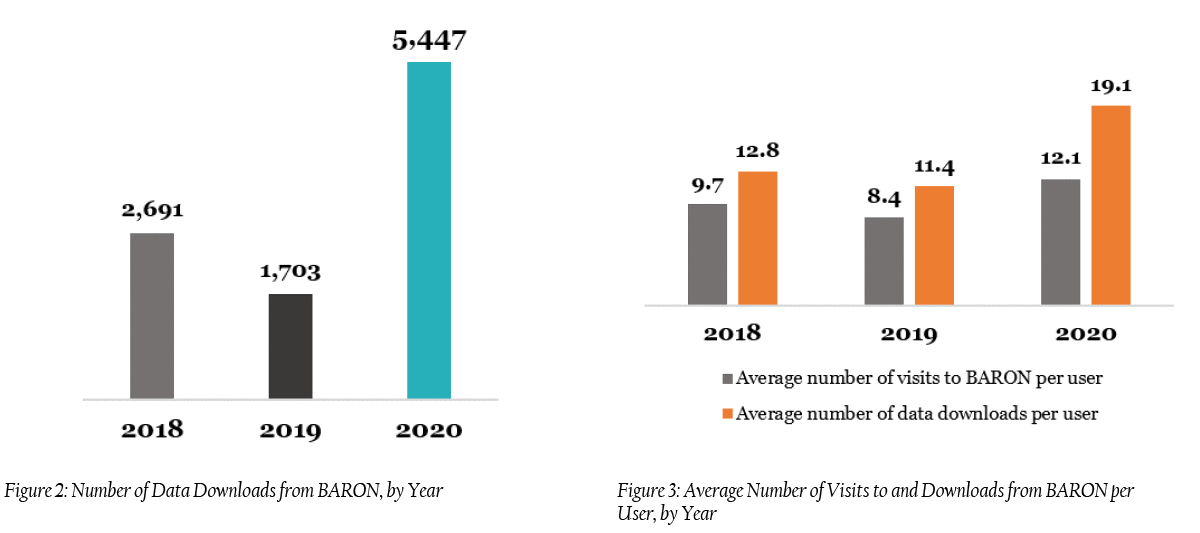

Auditors’ use of the system continues to expand, with an increasing number of teams planning audits after first confirming their feasibility by examining BARON data. From 2018 to 2020, the number of downloads from BARON more than doubled, and the average number of downloads and visits to BARON per user increased (see figures 2 and 3). Since 2020, when BAI improved the spreadsheet functions, the number of auditors using BARON has increased substantially.

While BAI established BARON to reduce barriers to conducting IT-based audits, auditors are still adjusting to the new system. To further promote BARON’s use, BAI needs to overcome two major challenges.

First, BAI is working with public institutions to ensure they enter accurate information into their databases, which in turn affects the quality of BARON data. Additionally, the Korean government has implemented the Act on Promotion of Data-driven Public Administration, which encourages digital transformation in the public sector. Given these collaborative efforts, BAI is optimistic about the prospects for IT-based audits. Second, it would behoove BAI to develop a feedback cycle, so that auditors and DDAIM can regularly share their views on how BARON can be most useful and effective.

With the audit environment experiencing significant changes due to both emerging technologies and the outbreak of the pandemic, BAI will continue its efforts to improve BARON and expand its use. By promoting IT-based audits, BAI aims to keep pace with the shift to e-government and ensure it can continue to fulfill its mandate and meet quality standards even in difficult circumstances.