Boost the Impact of Your Performance Audits: Building Blocks for a Theory on the Impact of Supreme Audit Institutions

By Prof. Dr. Sjoerd Keulen, Strategic Advisor, Netherlands Court of Audit and Professor by special appointment on Public Audit, Policy evaluation and Accountability on the Netherlands Court of Audit endowed chair at Leiden University. This article has been written in a personal capacity. The survey was conducted as independent academic research and not performed under the NCA’s mandate.

Introduction

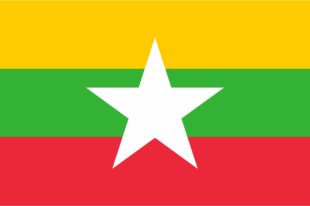

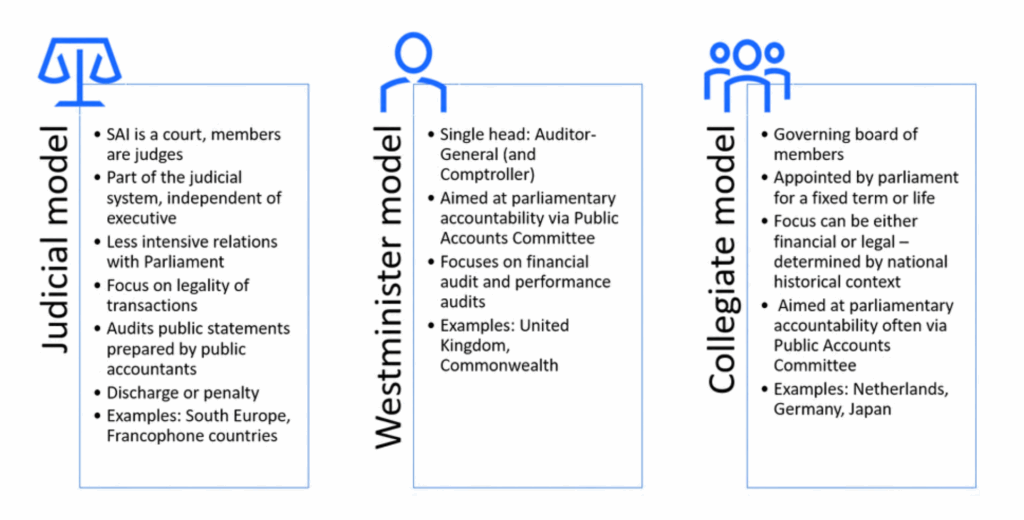

Many Supreme Audit Institutions (SAIs) have in recent decades adopted performance auditing as one of their main tasks. Performance audits extend a SAI’s role from main public auditor to judge, jury and even management consultant. INTOSAI has promoted performance auditing as a method to establish the economy, effectiveness and efficiency of government policy (‘the 3Es’) and a means to strengthen government accountability and transparency.

However, some critics say performance audits have not lived up to expectations, but have become a hollow ritual or led to nitpicking. The available evidence on the impact of performance audits is indeed ambiguous. Firstly, the wide range of audit designs makes comparisons difficult (Rana et al., 2022). Secondly, not all SAI governance models have been analyzed quantitatively and there is no evidence regarding the collegiate model, such as that at the Netherlands Court of Audit (NCA).

To assess the impact of the NCA’s performance audits of central government, we surveyed the performance audits carried out at all ministries in the Netherlands between 2018 and 2021. We used a scientifically validated survey that has been applied in Canada (Morin, 2014) and Belgium (DeSmedt et al., 2017), conducted by Valérie Pattyn and Minya Chan of Leiden University. Since the survey uses the impact model of Van Loocke and Put (2011), which lies at the heart of many quantitative studies of the impact of performance audits in different parts of the world, it can provide building blocks for a theory on the impact of SAI performance audits.

Before turning to the building blocks, we first explain the impact factors of performance audits and then present the key findings of the Dutch survey before providing the building blocks for a theory on impact.

Figure: The three governance models of Supreme Audit Institutions

Factors that Facilitate Impact

Impact lies at the heart of a SAI’s work, but ‘impact’ is a broad term with a range of meanings that need conceptualizing. The impact of performance audit is ‘the direct or indirect effect or influence that a SAI can have as a result of its performance audit work on the practices, performance, and culture of the audited entity’ (Lonsdale 1999, p. 171). There are generally thought to be three types of impact: instrumental, conceptual and strategic. These types of impact are non-exclusive and can overlap.

Instrumental impact is the use of performance audits to improve a process during or directly after the audit. The classic form of this impact is the acceptance and implementation of audit recommendations. Hence, this is why virtually every SAI counts how many of its recommendations are followed up.

Conceptual impact is about the lessons the auditee learns from the audit. Knowledge gradually influences policy in various ways in the medium to long term. The time span and subtleness of the change make it hard to measure the impact. Conceptual impact takes precedence over instrumental and strategic impact.

Strategic impact is the use of audit reports in discussions or negotiations as tools to influence decision-making, for example to escape from budget cuts.

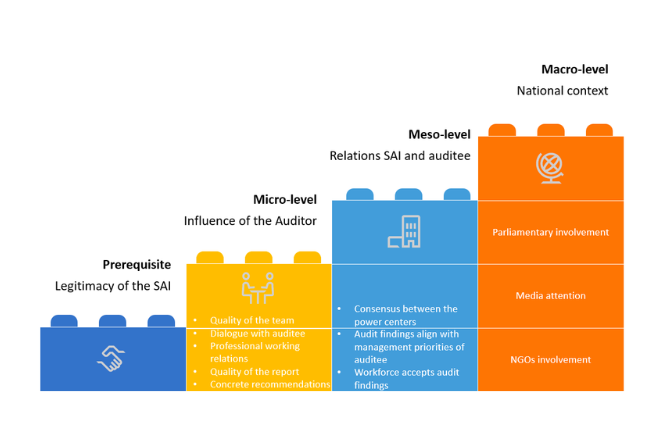

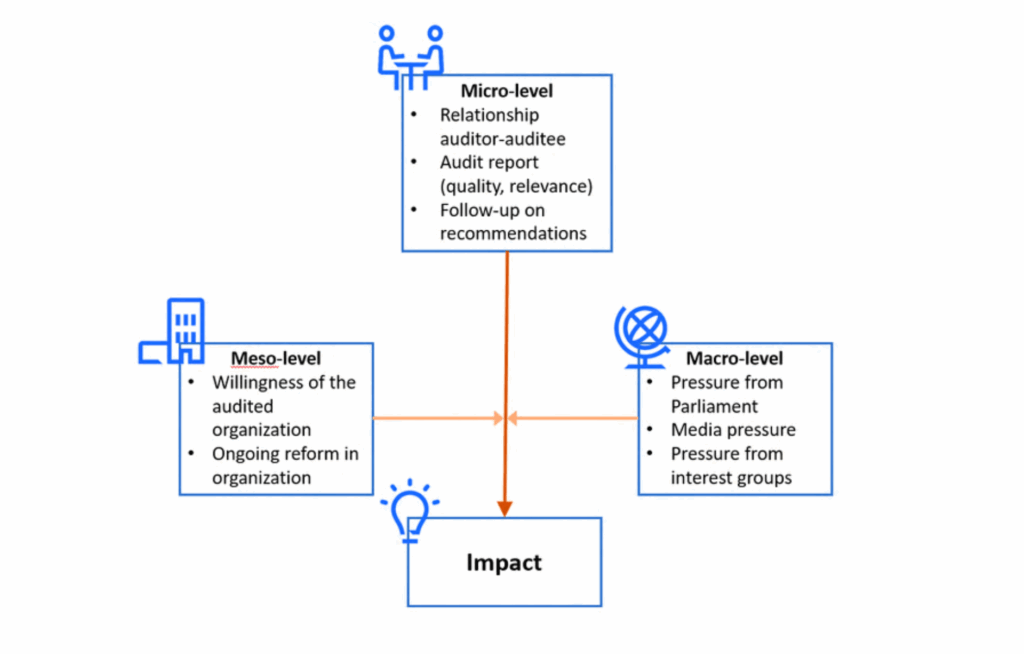

Impact is typically felt at three levels: the micro, the meso and the macro. The micro-level consists of factors relating directly to the audit itself. The meso-level covers the relationship between the SAI and the audited entity. The macro or national level comprises the sociopolitical context and the public sector characteristics in which the audit takes place.

Figure: The Impact Model of Performance Audits, based on Van Loocke and Put (2011)

The traditional and most common way to measure impact is to count the number of recommendations that are adopted. Adoption rates are high, but SAIs tend to rely on self-assessment by the auditees, and the number might be inflated. Another downside is that counting the adoption of recommendations takes only the instrumental impact into account and pays little attention to the complexity and sometimes long duration of any follow-up. Recent studies have therefore incorporated other impact-enhancing factors such as political accountability, resistance from the auditee and political or media debates.

Factors that Enhanced and Hindered Impact in the Netherlands

In the Netherlands, we used a tried and tested survey that takes all types of impact into account. Our first conclusion was that the NCA’s performance audits have a moderately positive impact on central government with a mean of 4.48 on a 7-point Likert scale (standard deviation = 1.29). This is similar to the impact of the Auditor General of Canada (Westminster model) and slightly higher than the Belgian Court of Audit’s 3.2/7 (judicial model). The nature of the impact was mainly conceptual, slightly instrumental and moderately strategic. In practice, this means that changes due to the audits were subtle and slow to emerge; this was also the case in Belgium and Canada.

Interestingly, a SAI’s impact is not always necessarily perceived as a positive thing. Some Dutch ministries reported a rise in operating costs with no increase in mid-term benefits. Furthermore, implementation of additional controls recommended in the audit report led to more dissatisfaction within the civil service.

At the micro-level, two key factors explained an individual auditor’s impact: firstly the auditor-auditee relationship and secondly the audit team’s expertise. Audits were more readily accepted if communication was open and professional. In particular, willingness to engage in dialogue with the auditee was important for acceptance of the audit findings in the Netherlands. If ministries perceived an audit team to be knowledgeable, its impact was much higher than if the auditee thought the audit team lacked expertise. A final important factor found in the literature is the quality of the audit report.

At the meso-level, impact is more likely if government and parliament and ministry managers and their staff agree about the SAI’s recommendations. If the audit findings matched the priorities of the Dutch ministry’s senior civil servants, they were more likely to be accepted. Implementation is always dependent on the willingness of civil servants and they will be more inclined to cooperate if they understand the need for and benefits of the audit recommendations.

At the Dutch national or macro-level, parliamentary involvement had a moderate impact, with both positive and negative effects. Parliamentarians could accelerate the pace of implementation, have shortcomings corrected and implemented real solutions to identified problems. However, parliamentary involvement sometimes had negative effects at the ministries, such as an increase in red tape or confusion of what parliament asked of the minister – which resulted in paralysis to handle.

Media attention is the second main determinant of impact at macro-level: it has reactivated political debate in the Netherlands and led to changes in central government. The impact has not always been positive. In some cases, media attention has disrupted an organization’s routine operations and – perhaps as window dressing or in attempt to look decisive – procedures have been tightened up.

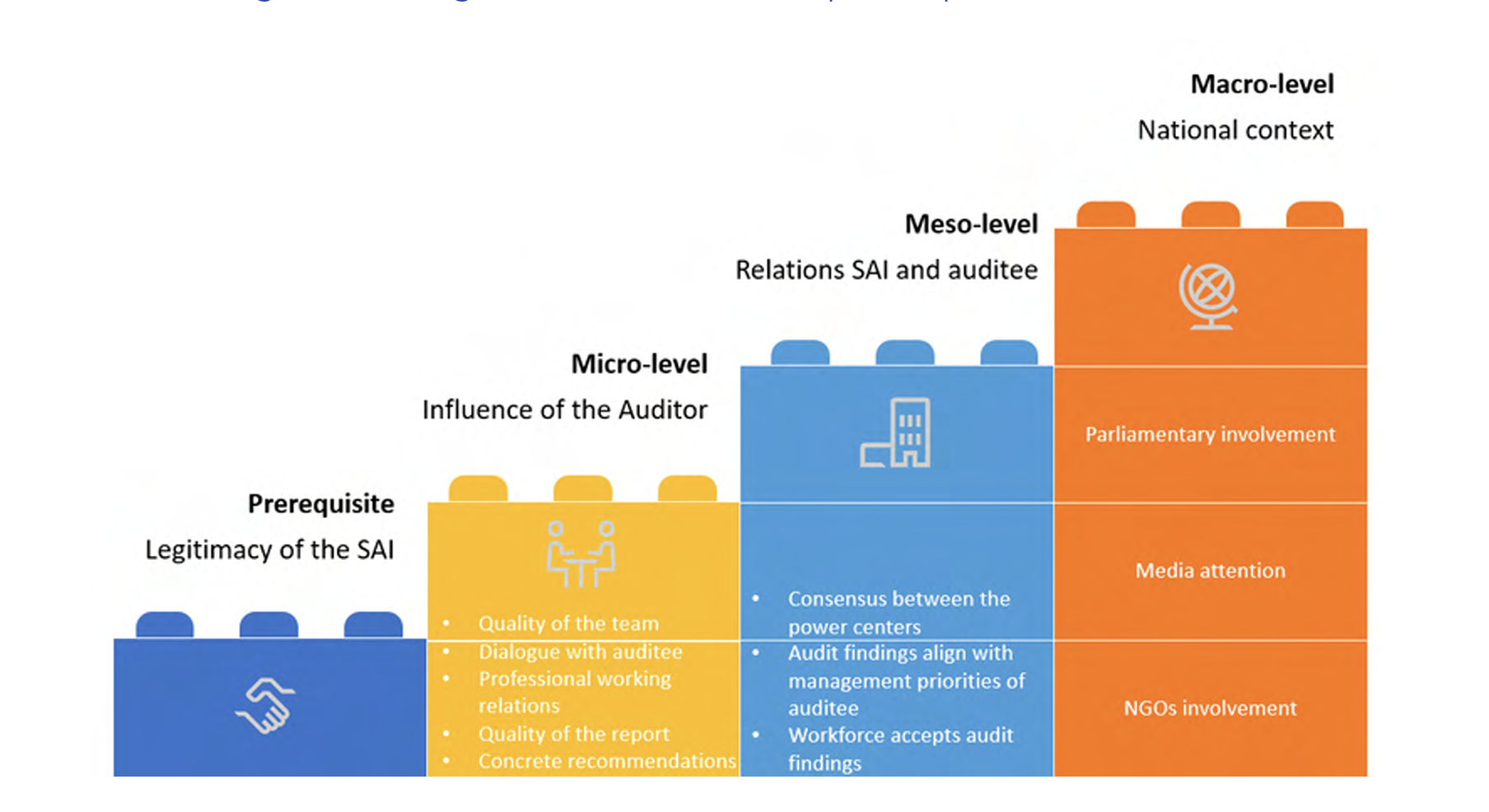

Figure: Building Blocks to boost the impact of performance audits

Building Blocks for a Theory on the Impact of Performance Audits on Public Administration

In this final section, we present building blocks for a theory on the impact of performance audits of SAIs. With the survey in the Netherlands, we now have a coherent and consistent body of evidence on all three SAI models, over a period of many years and from different parts of the world. We can therefore identify the most important impact factors for performance audits. A full literature review is needed to build a conclusive theory.

The prerequisite for impact is the legitimacy of the SAI. If a SAI is seen as a legitimate and important aspect of governance, the audit impact tends to be higher. This mechanism was demonstrated in both high-impact developed Scandinavian countries and in developing countries.

The quality of the audit team is a key predictor of impact at micro-level. Constructive interaction between auditor and auditee stimulates acceptance of the audit. A professional working relationship that strikes the right balance between the auditor and auditee’s independence and understanding can help stimulate this. The usefulness and quality of the audit report and recommendations are also important factors for impact. The more concrete the report’s recommendations, the higher its perceived value and thus impact.

Little research has been carried out on how to increase impact at the level of the auditee. One factor stands out: consensus between the different power centers. Consensus between the auditor, the staff at the bottom of the organization and the senior management and political leaders at the top is the best predictor of impact. The greater the consensus on audit findings and recommendations, the more likely impact seems to be.

At macro-level, many articles find that both parliamentary and media consideration of an audit boosts its impact. This is one of the reasons that INTOSAI promotes the involvement of media and parliaments. NGOs and civil society organizations are also increasingly being seen as channels to increase a SAI’s impact. Media attention boosted an audit’s impact in all the cases studied. In most cases, the impact was in the form of oversight, of holding someone accountable for the audit findings. Media and political attention does not automatically lead to changes in public administration. Media attention led to changes within an organization in only about half of the cases studied. As we saw at meso-level, senior management consensus and the willingness of the organization are critical if change is to take place.

Conclusion

Performance audits can have a positive impact on government organizations. The impact can be much broader than the typical implementation of audit recommendations. Audits can have a conceptual impact if they change the auditee’s way of thinking. Audits can also be used strategically to influence decisions. The impact begins with the individual auditor. The more professional and knowledgeable the auditor is, the more likely there will be a positive impact. His or her professionalism should be evident not only in a well written high quality report, but also in the willingness to communicate openly and engage in dialogue with the auditee. These micro factors also have an influence at the meso-level. If the organization and its management are not convinced of the necessity to alter their actions in response to the audit findings and recommendations, the less likely impact will be. Political consideration in parliament, the media or even the involvement of NGOs can help reactivate debate and have recommendations accepted, but even then the organization’s resistance can be too strong for it to change. This is what makes the individual auditor’s professionalism so important. The survey in the Netherlands and much of the academic literature show that professional conduct and open communication with the auditee can overcome an organization’s resistance and help get the audit recommendations accepted and implemented.