Board of Audit and Inspection of Korea (BAI) Audit Request System and its Implications for Public Participation

Source: Board of Audit and Inspection (BAI)

Author: Mr. Soungdae Park (Director, Audit Request Division 5), Board of Audit and Inspection of Korea

In identifying trends in public sector audit, there are two main changes in terms of audit types and stakeholders. Many supreme Audit Institutions (SAIs) have expanded their focus from compliance audits to include performance audits, and have strengthened their responsiveness to stakeholders’ concerns and needs. In the midst of social changes such as increasing participatory democracy and citizen involvement, the Board of Audit and Inspection of Korea (BAI) introduced the Audit Request for Public Interest (ARPI) in 1996, the Citizens’ Request for Audit (CRA) in 2002, and the National Assembly Audit Request in 2003. Audit Request Systems enable BAI to directly communicate with the public, whereas previously, BAI had indirectly influenced the public through its focus on auditing government agencies. SAIs’ main stakeholders are no longer limited to the Legislative, but has expanded to encompass all various parties including government agencies, lawmakers, media, citizens, and civil society organizations. This article introduces BAI’s audit request systems and explores its implications in the contemporary administrative system.

BAI Audit Request Systems

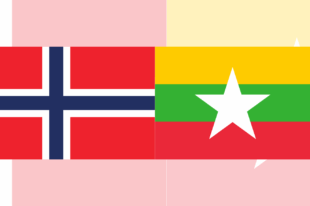

According to the ‘Regulation on Disposition of Audit Request for Public Interest’, BAI introduced the Audit Request for Public Interest (ARPI) in 1996 to receive audit requests on matters related to illegal activity, corruption, maladministration, waste of public funds, breach of public interests, etc. Individual citizens and civil society organizations can make audit requests if the number of requesters consist of more than 300 citizens aged 19 or older. The heads of public entities and local councils can also request audits to BAI. In 2002, the Citizens’ Request for Audit (CRA) was introduced with the ‘Act on the Prevention of Corruption and the Establishment and the Management of the Anti-Corruption and Civil Rights Commission. The CRA allows a group of more than 300 citizens aged 19 or older to request audit on the issues related to illegal activity and/or corruption of public entities.

Despite the similarities between ARPI and CRA, BAI maintains both channels as they are distinct from one another. For instance, ARPI is broader than CRA in terms of eligibility of requesters, and audit scope, amongst other things. CRA is limited to the audit requests on issues related to illegal activity and/or corruptions of public entities, but ARPI additionally covers matters related to unfair activities and wrongdoing of public entities. Furthermore, in determining whether or not to conduct an audit on the requested issues, in the case of ARPI, BAI alone reviews whether the request meets the eligibility and requirement. Comparatively, in the case of CRA, the ‘Audit Request Review Committee’, consisting of four external experts and three BAI executives, reviews and makes the decision on whether to conduct an audit on the requested issue.

Fig 1: Comparison of the Citizens’ Request for Audit and the Audit Request for Public Interest Systems

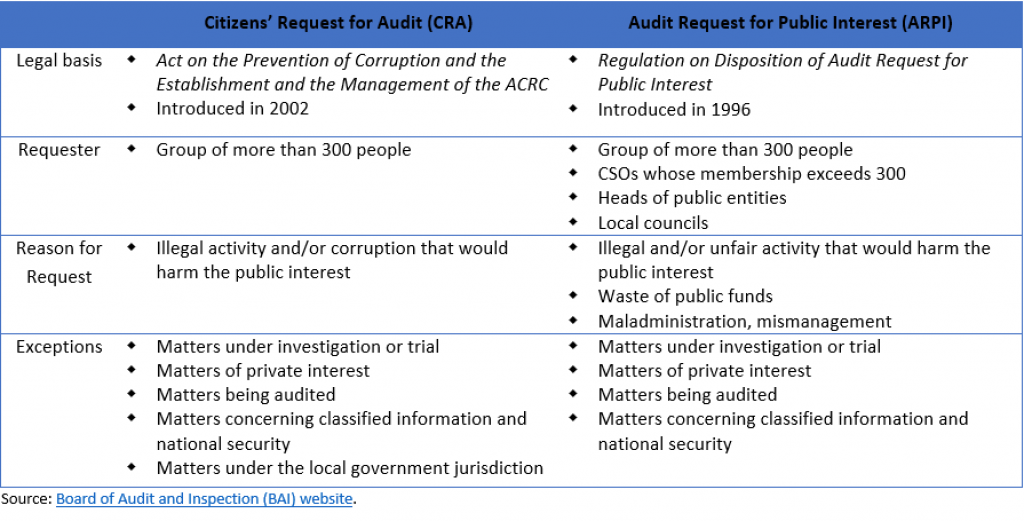

Since its introduction in 2002, the number of CRAs received has been fairly constant between 20 to 40 requests per year, whereas the number of ARPIs received has been steadily increasing. For example BAI received 16 ARPI cases in 1996, 126 cases in 2005 and 170 cases in 2020. This increase is partially attributed to the broader ARPI eligibility requirements, such as requesters and subject matter, compared to the CRA, thus making it easier for the public to access and request BAI audits. From 2002 to 2017, the number of received ARPI cases totaled to 400 cases – 113 cases were related to the construction and transportation sector, 47 cases on the education sector, 40 cases regarding the financial sector, 27 cases on environment sector and 173 cases on other sectors. BAI has carried out audits for 64 cases out of the 400 (16%).

Fig 2: Number of Received Audit Request for Public Interest (ARPI) Cases from 1996 to 2020

Source: Board of Audit and Inspection (BAI) ARPI case submissions

Implications

Participatory Democracy

In a modern democracy, elected representatives should be accountable to voters. Since the late 20th century, however, there has been criticism that elected governments have failed to fully respond to the people’s policy needs due to the acceleration of social change. In an effort to overcome this challenge of representative democracy, participatory democracy and deliberative democracy have gained attention. BAI’s audit request systems cannot be seen as direct public participation, nor as direct control by the people over the administration. However, it can function as a tool to strengthen participatory democracy in that it allows people and civil society to take engage in the decision-making process. Recently, BAI has observed an increase in audit requests on controversial local issues directly related to local residents’ benefits and convenience. It includes issues over where to place unpleasant facilities such as landfill sites, and whether to develop or preserve certain areas. Any inconvenience and/or dissatisfaction that people experience in their daily lives may increase their desire to participate in administration and the decision-making process. As citizens become involved in correcting unlawful or unreasonable administrative actions and decisions, BAI’s audit request system can be seen as a mechanism for people to actively engage in democratic practices, a concept emphasized by Alexis de Tocqueville.

External Control Function

Following the principal-agent problem, BAI’s audit request system allows people to request an audit, provided that it meets all request eligibility requirements, and can be a useful means for the citizens (the “principals”) to monitor and control public institutions’ (the “agents”) behavior. A principal-agent problem arises when there is a conflict of interest between the agent and the principal, which typically occurs when the agent acts solely in their own interests. The agent usually has more information than the principal, and such information asymmetry is one of the fundamental causes of the principal-agent problem. However, if it is observable and verifiable by principals that agents are pursuing their own interests, instead of those of principals, principals will try to control this behavior. In the context of the audit request system, a recent increase in audit requests can be interpreted as the citizens’ desire for monitoring the public institutions’ works.

Public Conflict Management System

Socially controversial issues may be challenging to manage due to competing interests, especially as an increasing number of stakeholders become involved. Public interests pursued by the government do not necessarily coincide with the personal interests pursued by individual. For example, relocation of an air force base can be seen as protection of public interests from the national security perspective, but at the same time it can be perceived as a violation of private interests from the land owners’ perspective. Likewise, conflicts between public interests and the interests of private property owners may often take place in the process of public policy implementation. It may be most desirable for public conflict to be managed through social agreement, but it becomes more complicated to resolve conflicts as the types of conflicts become more diverse and various stakeholders get involved.

Despite the conflict management mechanism operated by the Office for Government Policy Coordination, BAI has observed an increase in audit requests on socially controversial issues in recent years, as people want such issues to be addressed through BAI’s audit request system. For example, the audit request system has received multiple requests for the Four Major River Project and new airport construction project. The public’s trust in the BAI enables the audit request system to serve as a public conflict management system.

Audit Request Case Study

Background

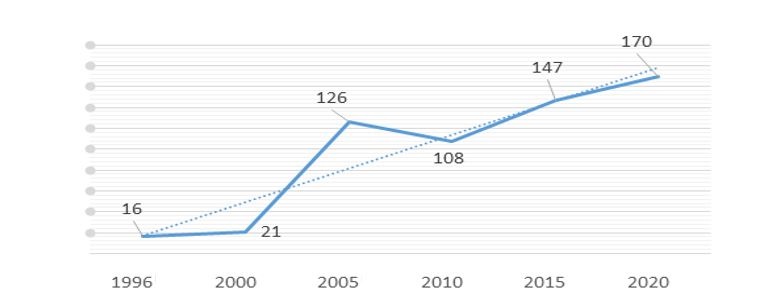

As of 2017, 99 people lived in Jangjeom village in Iksan city, Jeollabuk Province, South Korea. 45 of these 99 people were above the age of 60, and 22 out of these 99 residents have been diagnosed with cancers with 14 of them passing away. A fertilizer factory, named Geumgang Nongsan, had operated near the village and produced fertilizer between 2009 and 2016.

Fig 3: Jangjeom Village Map

Source: Board of Audit and Inspection (BAI)

Timeline

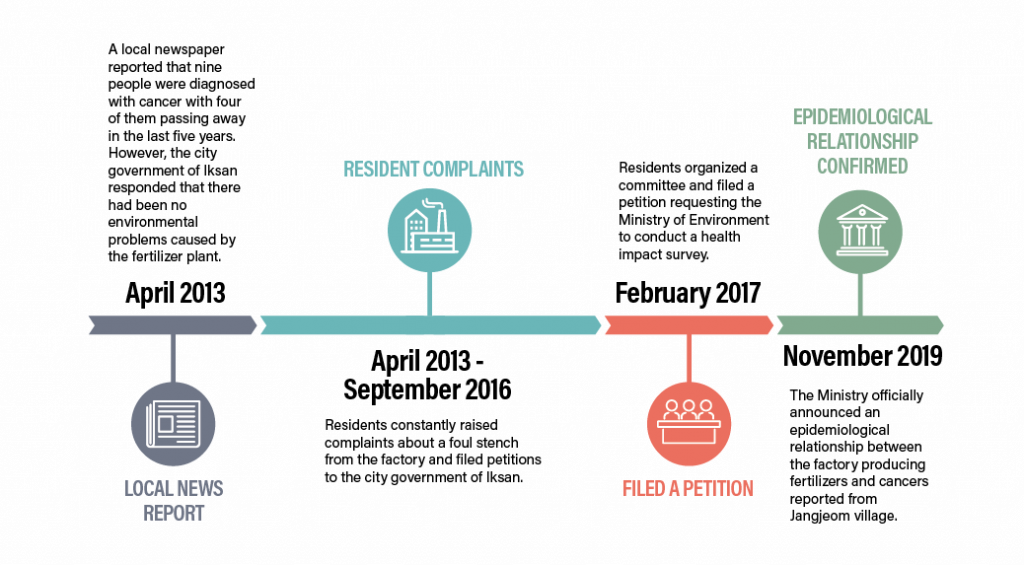

Fig. 4: Jangjeom Village Audit Request Timeline

Source: Board of Audit and Inspection (BAI)

- In April 2013, a local newspaper reported that nine people were diagnosed with cancer with four of them passing away in the last five years. However, the city government of Iksan responded that there had been no environmental problems caused by the fertilizer plant.

- From April 2013 to September 2016, residents constantly raised complaints about a foul stench from the factory and filed petitions to the city government of Iksan.

- In February 2017, residents organized a committee and filed a petition requesting the Ministry of Environment to conduct a health impact survey.

- In November 2019, the Ministry officially announced an epidemiological relationship between the factory producing fertilizers and cancers reported from Jangjeom village.

Audit Request and Result

In April 2019, residents requested BAI to conduct an audit on the Iksan city government and the Jeollabuk provincial government, as they believed that the governments had not only neglected their duty to supervise the factory but also had not taken administrative measures until Jangjeom village received media coverage.

BAI found that the negligence of the local government had contributed to the formation of a cancer cluster in Jangjeom village, and thus recommended that disciplinary penalties be imposed on public officials.

Conclusion

BAI aims to improve transparency and impartiality in public administration by encouraging citizens to participate in and monitor the public administration of the central government, local governments and public institutions. By operating the Audit Request System, BAI also strives to satisfy the need of citizens by rapidly resolving matters that disrupt the lives of the public. The Audit Request System contributes to ensuring transparency and impartiality in the public sector by fittingly and actively responding to changing audit demands and deriving timely audit results.