Beyond auditing and reporting – the expansion of the Auditor-General of South Africa’s powers to strengthen accountability mechanisms

Author: Thabelo Khangale, Deputy Business Unit Leader: Material Irregularity Unit, Office of the Auditor-General of South Africa

1. Introduction

Following a number of years of deteriorating audit outcomes and a lack of consequences for the mismanagement of the public funds by those charged with the governance of government entities, the public demand for enhanced accountability and transparency saw calls from the public, media and parliamentary oversight structures for a review of the mandate and powers of the Auditor-General South Africa (AGSA) to go beyond auditing and reporting in an effort to strengthen accountability mechanisms.

In April 2019, the Public Audit Act (PAA)(1) was amended to give the AGSA the power to identify and report on material irregularities and to take action if accounting officers and authorities in charge of the government entities fail to address the material irregularities appropriately. The amendments introduced an enforcement mechanism to strengthen public sector financial and performance management so that irregularities (such as non-compliance, fraud, theft and breaches of fiduciary duties) identified during our audits and their resultant impact can be prevented or can be dealt with appropriately and without undue delays.

When the AGSA was established more than a hundred years ago, South Africa adopted the Westminster system, also known as the Anglo-Saxon or Parliamentary model, when designing our institution. This model is employed by most Commonwealth countries.(2) Under a Westminster model, the work of the Supreme Audit Institution (SAI) is intrinsically linked to the system of parliamentary accountability. The basic elements of such a system are production of annual financial statements by all government departments and other public bodies, the audit of those accounts by the SAI and the submission of audit reports to Parliament for review by a dedicated committee.(3) With the 2019 amendments to the PAA, the AGSA is no longer a SAI based purely on the Westminster system. It also enjoys enforcement powers that are internationally recognised as jurisdictional functions. This means that we will continue to do what we have done in the past (auditing and reporting), but with the additional mechanisms of strengthening accountability as set out below in more detail.

2. Key changes brought by the amendments to the PAA

Until 31 March 2019, AGSA’s work consisted of auditing and reporting on the outcomes of audits to those accountable for public accounts, as well as to relevant oversight structures. Our audits also generated commitments from stakeholders to address the root causes giving rise to the audit findings so reported. The amendments that commenced on 1 April 2019 have not changed this position. We must continue with our auditing and reporting obligations and continue to solicit commitments for improvement. The amendments do, however, introduce a number of new mechanisms to ensure that audit findings are properly addressed and recommendations are implemented.

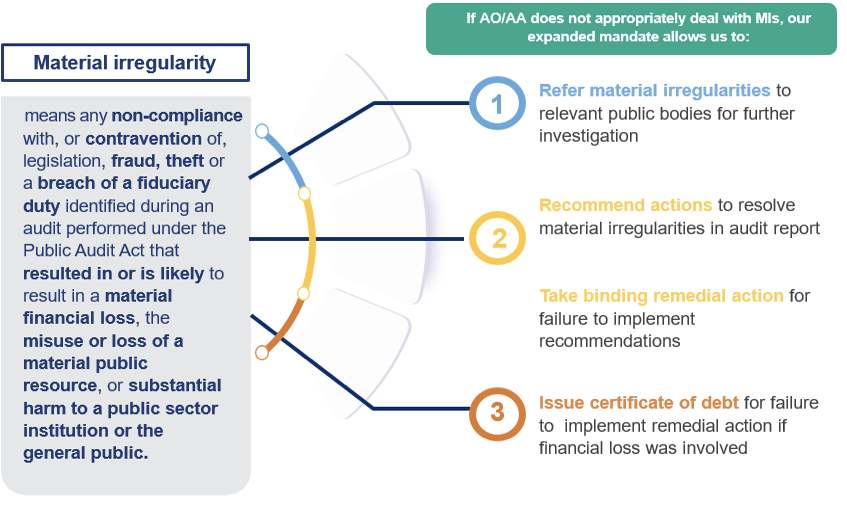

At the heart of the amendments is the concept of “material irregularity” (commonly referred to as “MI”). But what exactly is an MI? What happens once an MI has been identified? The definition of an MI and possible actions that can be triggered by an MI are reflected in Figure 1.

The definition contains three elements. Firstly, there must be a form of breach. The breach can come in the form of non-compliance with the law or in the form of a criminal act such as fraud or theft. Even a breach of a fiduciary duty is sufficient to satisfy this element of the definition. The second element of the definition is the proximity of an MI to the audit process. In fact, an MI can be identified during the course of an audit performed in terms of the PAA. Thirdly, not all breaches identified during the course of an audit under the PAA constitute MIs. The breach must have a material impact.

The amendments not only introduced the concept of MI in the work of the South African SAI, but also require the Auditor-General to act promptly once an MI has been identified.

- Referral on MIs to relevant public bodies

The PAA provides that the Auditor-General may, as prescribed by regulation, refer any suspected material irregularity identified during an audit performed under the PAA to a relevant public body for investigation, and the public body must keep the Auditor-General informed of the progress and the final outcome of the investigation.

- Remedial action

If the Auditor-General detects an MI during an audit, but decides not to refer it to a public body for investigation, he or she may make recommendations in the audit report regarding the best possible ways to address the MI. These recommendations aim to assist the accounting officers and authorities of the relevant public institution to address the MI. The Auditor-General must, within a stipulated time, follow-up on the recommendations made in the audit report. If the accounting officers and authorities fail to implement the recommendations, the Auditor-General must issue binding remedial action, instructing the accounting officer and accounting authority to act on the initial recommendations made within a stipulated time. If the MI involved a financial loss to the state, such remedial action must include a directive or instruction to the accounting officer and authority to quantify and recover the loss from the responsible person, again within a stipulated time.

- Certificate of debt

In the event that the Auditor-General issued a directive to the accounting officer and authority to quantify and recover a loss to the State from a responsible person, and the accounting officer and authority fails to do so within the stipulated time, the Auditor-General can issue a certificate of debt against the accounting officer and authority. The certificate of debt effectively renders the accounting officer and authority a debtor to the State and the amount specified in the certificate must be paid by the accounting officer and authority in his, her or their personal capacity. Once the certificate of debt has been issued, the Auditor-General must submit a copy thereof to the responsible executive authority, who is charged with the responsibility to recover the certificate amount from the accounting officer and authority. The executive authority must keep the Auditor-General informed of the progress made with the recovery of the amount.

Before the Auditor-General can lawfully issue a certificate, he or she must invite the implicated accounting officer and authority to make written representations to the Auditor-General, citing reasons why such a certificate should not be issued. If the Auditor-General, after considering the accounting officer and authority written representations, still considers a certificate of debt appropriate, he or she must establish an independent advisory committee to hear oral representations from the accounting officer and authority. The Auditor-General can only issue the certificate of debt after due consideration of the written recommendations of the advisory committee.

3. Strategies for implementation

A change in the legal framework of any SAI requires careful consideration of the potential impact thereof on the SAI’s internal and external environment. Although our audit process remains largely the same, the new powers of referral, remedial action and certificates of debt required an assessment of the impact thereof on our environment, both internally on our people and operations, and externally on our stakeholders. Furthermore, the necessary practical tools, such as regulations, policies, procedures, structures, etc. for efficient and effective implementation had to be put in place prior to implementation.

The amendments no doubt had an impact on the institution’s available skills and capacity. We developed a comprehensive technical and soft skills training programme to prepare our audit and support staff prior to the commencement of the amendments and began recruiting staff with specialised expertise required to manage the MI process. The successful implementation of statutory changes often hinges on the strategies in place, and how well an institution prepares those affected by the changes. We developed a comprehensive internal and external stakeholder engagement plan that covers our staff, accounting officers and authorities of our auditees, oversight structures, regulators and professional bodies. Due to the novelty of these extended powers, and our capacity constraints, we obtained the blessing of the Parliament’s Standing Committee on the Auditor-General to phase in the implementation of MI process to a certain number of our auditees during the first year of implementation.

Notably, we also aligned our organizational strategy to ensure that it complements the implementation of the new powers. The AGSA’s new long-term strategy (#CultureShift 2030)(4) aspires to have a more direct, stronger and consistent impact on improving the lives of ordinary South Africans by helping to improve the public sector culture through insight, influence and enforcement of the new powers. Success in this regard does not only rest on our ability to fulfill our mandate, but also on the extent to which we are able to mobilize and bring the collective influence of the whole network of stakeholders responsible for public sector accountability to drive positive change.

4. Impact of material irregularity process

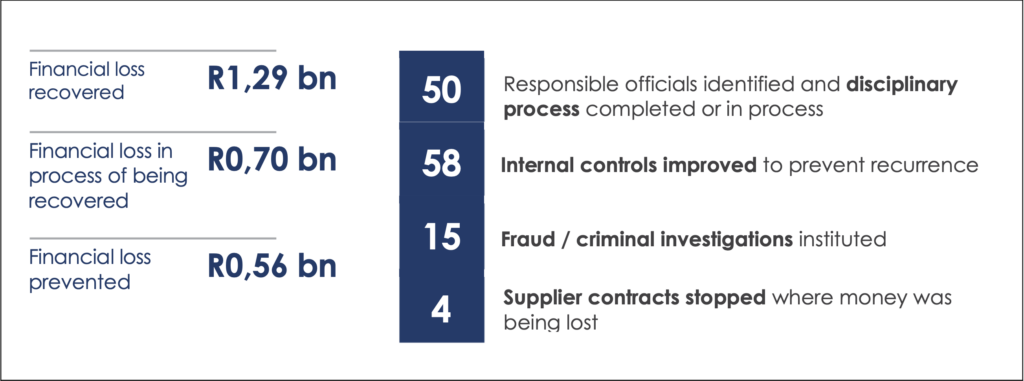

Since the implementation of the MI process, accounting officers and authorities have taken action to prevent or recover financial losses, while some of the losses are still in the process of being recovered. We have noted implementation of consequence management against officials responsible for the financial losses, including the referral of matters to law-enforcement agencies. Improvements in the systems, processes and internal controls to prevent any further financial losses have been noted. In the 2022-23 general report for national and provincial departments, their entities and legislatures tabled in Parliament, the Auditor-General reported the following actions taken to address the financial loss. (See figure 2)

5. Conclusion

The amendment of the PAA is one of the biggest success stories for the AGSA. This would not have been possible without the strategies of implementation highlighted above. Amongst other things, we will continue to measure the success of the amendments to the PAA against the characteristics of the public sector culture that we aspire to see and work towards, that is a public sector that is underpinned by a culture of performance, accountability, transparency and integrity.

The AGSA has a constitutional mandate and, as the SAI of South Africa, exists to strengthen our country’s democracy by enabling oversight, accountability and governance in the public sector through auditing, thereby building public confidence. This is our mission, but, without a shared vision for accountability by the whole of the accountability ecosystem in the public sector, no law will be able to realize this mission. The implementation of the new powers remains a continuous journey for the AGSA. However, the organization is encouraged by the positive actions that many accounting officers and authorities have already taken to ensure that MIs are addressed, resulting in an improved accountability culture within the public sector.