Author: Claire Schouten, International Budget Partnership

Introduction

Efficient and effective utilization of public funds and resources is essential for all countries to achieve their development targets. Government auditors, led by national supreme audit institutions (SAIs), play a critical role in monitoring the utilization of these resources. SAIs are countries’ top watchdogs on government finances and are mandated, often by national constitutions, to scrutinize whether governments are managing public funds properly. SAIs conduct financial audits that examine the legality of financial transactions and performance audits to assess whether public funds have been used efficiently and effectively. Audit reports issued by SAIs contain recommendations on how to improve financial management.

Unfortunately, many governments do not respond favorably to audit findings and often ignore important recommendations. Convincing and incentivizing more governments to address these findings could strengthen audit systems and enhance the effectiveness and efficiency of national budget systems.

The International Budget Partnership (IBP) and our partners in various countries have worked together with SAIs to analyze audit follow-up, improve communication of audit recommendations, and enhance engagement between key oversight actors from within and outside government to promote action on audit recommendations.

An important element is advocating for the timely publication of audits and greater transparency of the remedial actions taken by governments to address adverse audit findings. We see some progress in the latest Open Budget Survey, which shows a small increase in the timely publication of audit reports, with 81 of 125 assessed countries (68%) publishing on time.

Quality audit reports are also essential for identifying the specific reforms needed to strengthen public finance systems. As highlighted in a handbook developed by SAIs, the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs and IBP, audit reports should explain why (causes) and how (effects) the problems identified (findings) affect the performance of the auditee, and how to address those causes through specific corrective actions (recommendations). This requires not only focusing on the audit findings but, where applicable, also on the recommendations formulated to correct the problematic situations. Pinpointing the causes and effects of an audit finding is essential for an audit to ultimately generate impact.

While SAIs need to be interconnected within the accountability ecosystem, they also need independence from the executive. Since the last Open Budget Survey, we see a concerning drop in the 120 countries assessed in both rounds in the independence of the appointment of the SAI head, from an average score of 69 to 63. We also see a similar drop in the removal of the SAI head from office, from 78 to 76.

Achieving Accountability through Audits

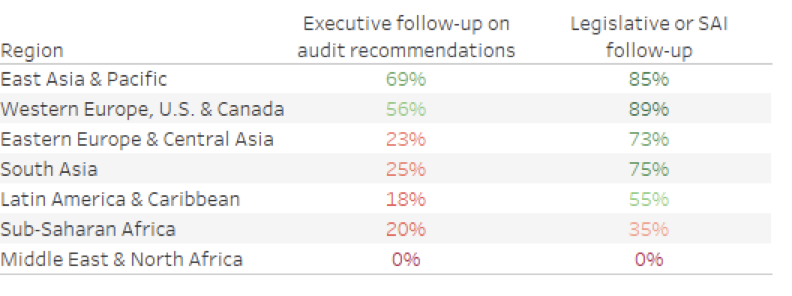

Lack of follow-up on audit recommendations is a widely recognized issue, but its extent is hard to quantify as the majority of countries do not keep records of government actions to resolve these recommendations. As shown in the figure below, legislatures or SAIs are more likely than executives to publish follow-up reports on audit recommendations.

Percentage of countries by region in which the executive and/or the legislature or SAI makes an effort to follow up on audit recommendations

Note: Percentage of countries by region, with publicly available audit reports, which make some effort at follow-up on audit recommendations.

Few global studies examine why governments do not follow up on audit recommendations. Various experts suggest that governments typically do not face enough pressure internally or externally from legislatures or the public to implement audit recommendations. They also agree that improved accountability requires stronger oversight actors and systems that enhance engagement among them. On the other hand, officials may view audits as threats to their powers rather than as tools that can improve the effectiveness of their operations. Defensive actions from government officials to audit findings are often a sign that the recommendations will be ignored.

We need all hands on deck

Effective audit and oversight systems require reforms by all actors in the system. Some reforms will need to address SAIs’ resource constraints. But SAIs, legislatures, civil society, and development partners can also take other actions to improve weaknesses in audit and oversight systems.

Developing and implementing communication strategies on the key findings and remedial actions from audit reports is one tactic SAIs can use to encourage government action. Our experience fostering collaboration between SAIs and civil society on audit follow-up and case studies on successful audits from Argentina, India, and the Philippines show how effective communications strategies helped create an environment where governments could not ignore audit findings.

SAIs can also help mitigate some of the weaknesses surrounding legislative scrutiny of audits. For example, the SAI leadership can take steps to limit the politicization of audits by ensuring that audit findings are relevant to decision makers, are presented in a non-partisan manner, and are clearly based on proven facts. Further, SAIs can help legislatures understand technical audit reports, suggest questions on recommendations that can be used to query executive officials in legislative hearings, and draft letters that legislatures can use to follow up on the status of recommendations. Within the legislature, the leadership can prioritize audit discussions and provide guidance on audit scrutiny. Budget oversight and audits can also be connected by using audit results to inform subsequent budget allocations. For example, in the Netherlands, the head of the SAI presents a report to the national legislature on an “Accountability Day” held in May that reviews each ministry’s performance. These deliberations then inform legislative budget allocation discussions in September.

SAIs can also work with civil society and other stakeholders to engage the media on government or legislative inaction on audit findings. SAIs and other actors can develop databases to catalog audit findings and remedial actions. For example, the SAI of the United Kingdom has a recommendations tracker to monitor government responses to its audits. In Malaysia, the Auditor General’s dashboard includes a simple overview chart for each ministry, which shows the number of audit issues and indicates their status by color. The public can navigate the database and not only see comments by the ministry, but also provide direct feedback. SAIs in Georgia, Indonesia and the United States are also leveraging electronic monitoring to improve action on audits. Such tools can help bring attention to audit findings that are being ignored.

SAIs can also send periodic letters to the heads of agencies informing them of the priority recommendations that are still open at their agencies and urging their personal attention. SAIs can use implementation rates of audit recommendations as performance indicators and report on the impact of implemented recommendations, which can demonstrate how action leads to positive results. SAIs and other stakeholders can advocate for the enactment of legislation requiring the reporting of corrective actions taken by government in response to audits.

Public engagement, especially with marginalized communities, throughout the audit process can help identify critical audit topics, generate evidence for investigations, develop meaningful recommendations, simplify audit findings, and build pressure for action. Across Argentina, Colombia, France, The Gambia, Ghana, Nepal, Peru, Philippines, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Tanzania and other countries, we have seen promising results when SAIs and civil society come together to strengthen accountability and the impact of audits.

Recommendations

The coming years will see countries face multiple demands on public resources – managing higher interest rates, geopolitical risks, and increasing climate vulnerabilities. Investments to strengthen oversight institutions are essential to ensure governments are making the most of their resources. Immediate steps are needed to preserve the independence of SAIs, enhance public engagement in audit and oversight processes, and improve the review and follow-up of audit reports.

We urge SAIs to make every effort to publish their audit findings and to create meaningful and inclusive mechanisms for civic engagement. This could be achieved by working with civil society groups to improve audit targeting, expand coverage, and enhance capacity.

Legislatures should review and follow-up on audit reports and hold public hearings with SAIs and the public. They should also ensure that SAIs have the mandate, independence and resources to conduct and publish relevant, high-quality audits on the use of emergency funds.

Civil society should champion the independence of SAIs and call out governments when audit independence is threatened. They should also engage with SAIs in a dialogue on priority and high-risk areas for audit, promote the visibility of audit reports and recommendations, and urge the executive branch to take action on audit findings.

Development partners should explore opportunities for support to all institutions that form the audit and oversight ecosystem and push back when the independence of SAIs in partner countries is threatened.

Finally, governments should direct audited public organizations to make all information available to auditors, and take appropriate action on audit findings.

Together we can leverage our strengths to unleash the power of public audits and oversight.