Crisis Management System on Rail Networks in Poland

Author: Iwona Zubrzycka-Wasil, Supreme Audit Office of Poland

The audit of crisis management functioning within rail infrastructure was undertaken on the Supreme Audit Office of Poland, Najwyższa Izba Kontroli (NIK)’s own initiative and covered among other, procedures applied during the biggest breakdown of rail traffic control that occurred in March 2022, 3 weeks after Russia invaded Ukraine. The audit was also driven by a significant number of issues and accidents on railways. In 2020, 516 railway accidents occurred, of which 6 were serious accidents caused by collisions or derailment of trains and affected the safety of people within railway areas. Moreover, 1,218 incidents were noted that did not result in any fatalities or serious injuries or in material or environment damage. However, these incidents could have turned into events requiring actions provided for in crisis management plans. The also audit investigated issues identified during the mass coal transports from seaports at the turn of 2022-2023, issues related to movements of refugees from Ukraine, difficulties in rail traffic in the area of Warsaw Junction caused by investment works in 2020-2023 and disturbances in rail traffic caused by an unauthorized broadcasting of radio-stop signals in 2020-2023.

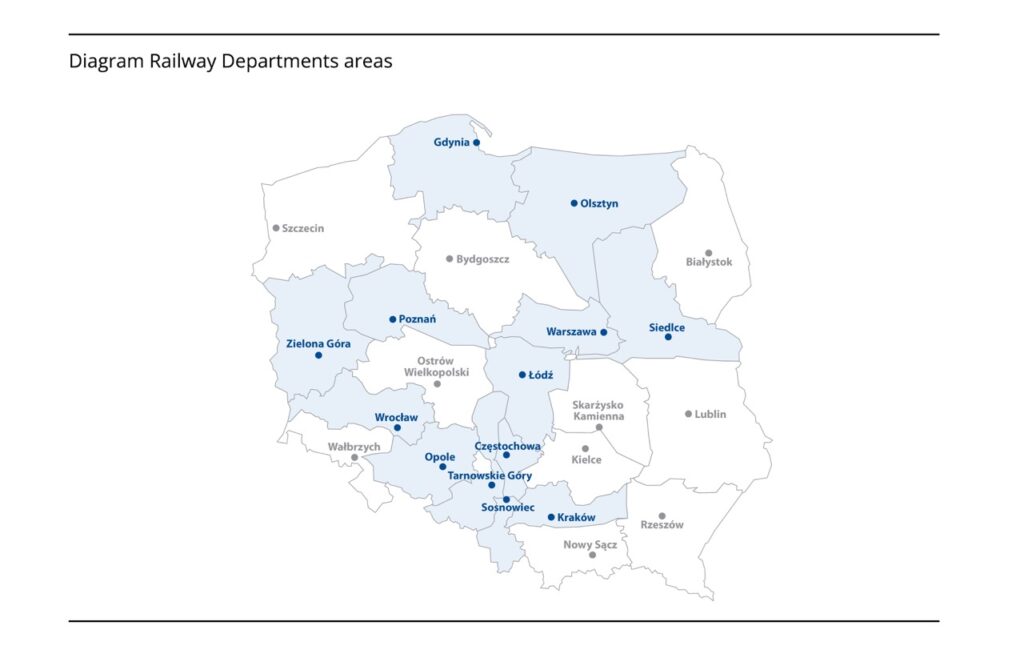

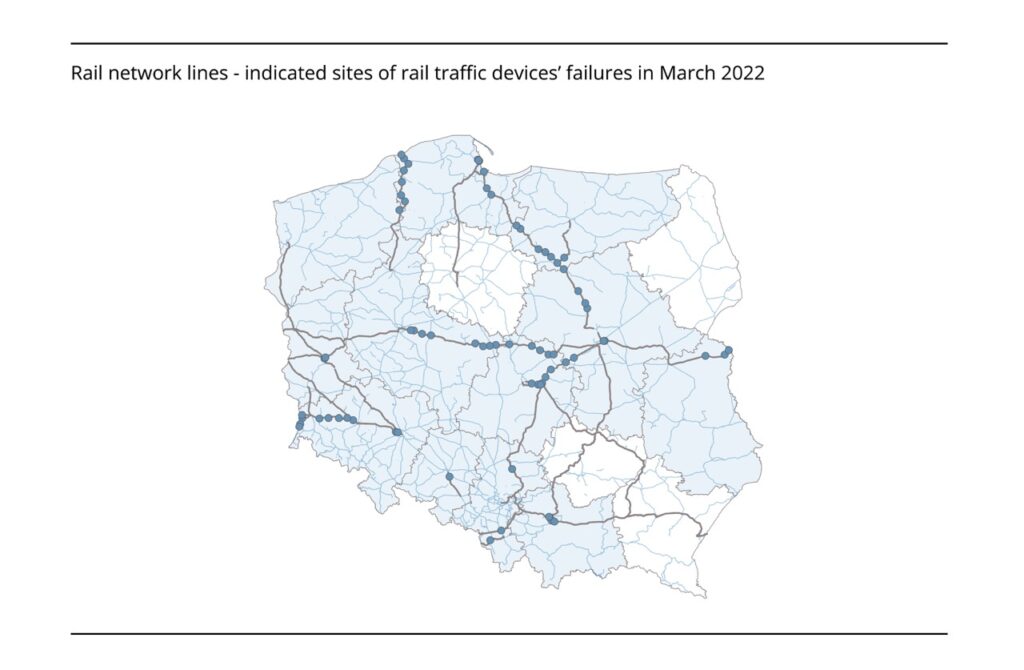

The nationwide railway traffic control breakdown in March 2022 was related to a failure of electronic traffic control systems, which yielded the suspension of rail traffic on approximately 80% of railways. The breakdown covered a total of 1,123 kilometres of lines and stopped rail traffic control of 13 out of 23 Railway Departments. 457 trains were recalled, and 1,328 trains delayed, with delays often exceeding 2 hours. 19 rail traffic management system centres were not operating. This event took place during the third level of CRP threat, the Charlie and Code Red terrorism threat at the main Polish Rail Lines Operator, PKP PLK S.A., after Russian aggression on Ukraine.

Diagram 1-Railways Departments areas affected by the breakdown of 17 March 2022

Diagram 2 – Rail network lines – indicated sites of rail traffic devices failures in March 2022

The rail transport system is an essential component of critical infrastructure. The main goal of protecting railway networks is to maintain continuity of services crucial for state and citizen security and for the efficient functioning of administration, institutions and business.

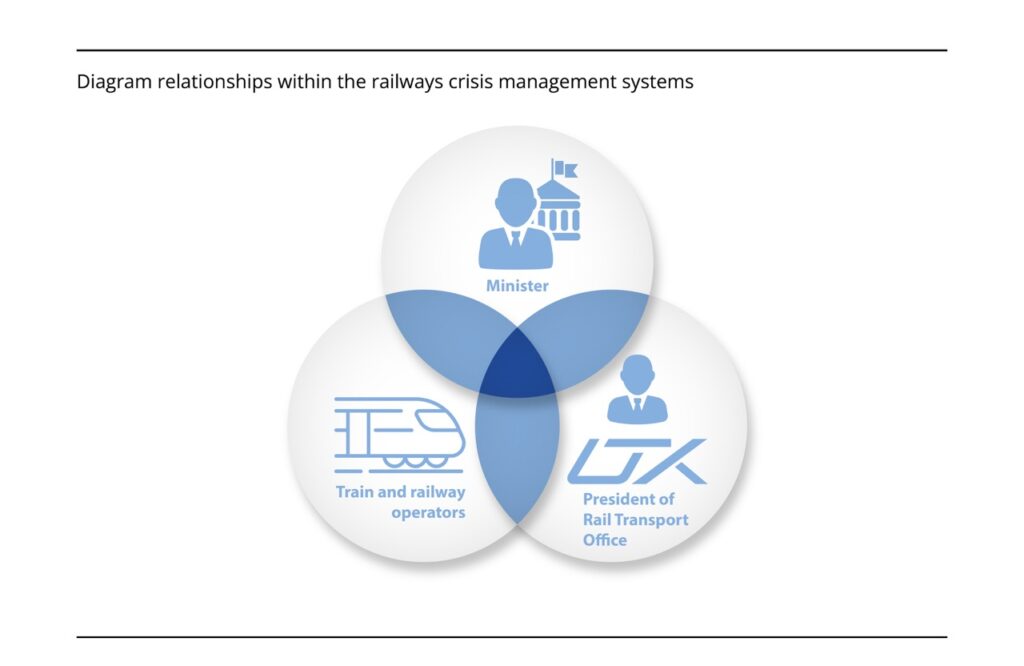

For this audit, NIK identified 3 main systems of crisis management on the rail networks:

- The crisis management system of the Minister of Infrastructure, in charge of transport,

- The safety management systems (SMS) of railway infrastructure operators (lines, stations),

- The SMS of trains operators (carriers, vehicle maintenance services).

The NIK’s audit purpose was to issue an opinion on whether the crisis management systems guaranteed appropriate protection of critical infrastructure and passenger safety in trains, rail stations and rail areas, through answering the following questions:

- To what extent did the management system adopted and applied by the rail lines and infrastructure manager PKP PLK S.A. ensure proper and effective preparation of the infrastructure, proper management of railway traffic and safety of persons on railway premises in the case of crisis situations?

- To what extent did the management system adopted by train operator, including its organization, tools and procedures, ensure the safe operation of railway vehicles and railway infrastructure and the safety of passengers in crisis situations occurring on the railway?

- To what extent did the rail stations operator PKP S.A ensure proper organization, tools and procedures, allowing for maintenance and protection of rail stations and safety of people within rail area in crisis situations?

- To what extent did entrepreneurs providing services necessary for rail transport functioning, including IT, telecommunications and energy supply, to the benefit of rail infrastructure managers, railway station managers and rail carriers, have an organisation, resources and procedures to ensure safe operation in crisis situations on the railway, in the segments of the rail system entrusted to their service?

- Did the Minister responsible for rail transport correctly and reliably perform his tasks related to the supervision of rail transport safety in crisis situations occurring on the railway network?

The audited period was from 2020–2023. Audited units’ selection was purposeful and came from identified issues that occurred in a given area. The audit covered the following infrastructure operators, trains operators and authorities in its scope:

- Minister of Infrastructure,

- National Railway Network Manager, PKP PLK S.A.,

- Rail Stations Manager of PKP S.A.,

- Rail operators: PKP Informatics, PKP Telkol, PKP Linia Hutnicza Szerokotorowa,

- Rail carriers: Koleje Mazowieckie, Polregio, Koleje Wielkopolskie, Koleje Śląskie, PKP Szybka Kolej Miejska w Trójmieście, Arriva sp. z o.o.

During this audit upon NIK’s request, the Office of Rail Transport performed a series of ad hoc audits of the functioning of safety management systems (SMS) of the following operators:

- PKP Cargo S.A. (freight),

- PKP Intercity S.A. (passenger),

- PGE Energetyka Kolejowa S.A. (energy supply),

- and in eight PKP PLK S.A. Railway Departments (rail lines maintenance).

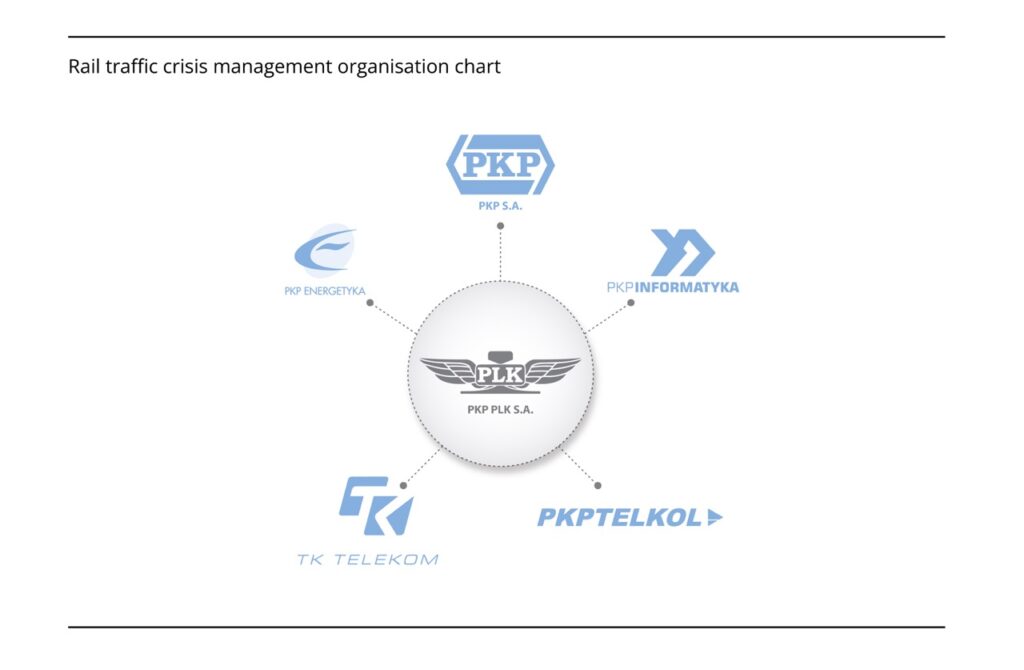

3. Diagram relationship within the railways crisis management system

Audit results

NIK’s audit found that the Minister responsible for rail transport did not ensure an effective operation of the crisis management system on railways, which created a risk of improper functioning of critical infrastructure protection and safety of people within the railway area, rail stations and in trains, as well as of residents of towns located on the rail routes of transportation of dangerous goods.

The crisis management system implemented by the Minister did not ensure coherence and full correlation of actions taken on the basis of various regulations. The areas lacking coherence included the statutory crisis management system, the railway system for managing crisis situations and the safety management system.

The Minister did not specify principles or procedures for cooperation with railway companies in the statutory crisis management system on the railway. The activities of these railway entities were an essential link in ensuring the effective functioning of the entire crisis management system. The Minister did not identify, and in any way qualify in the crisis management plan rail transport risks or crisis events on the railway, which allowed the possibility of destabilizing appropriate critical rail infrastructure system functioning caused by its destruction or disruption. The Minister identified similar risks and events in the area of road transport, yet did not do so for the railway.

The Minister did not take effective actions to define or agree (e.g. in the form of an agreement or understanding) the principles and procedures for the organization and functioning of railway companies and entrepreneurs operating within the crisis management system within the government administration transport department. The improper functioning of the crisis management system was confirmed by Minister’s failure to classify the rail traffic control breakdown in 13 out of 23 PKP PLK S.A. railway line departments. In such crisis situations, the Minister did not launch his own crisis management procedures on the railway network.

The cooperation of the bodies legally obliged to develop crisis management plans for railways (i.e. Minister of Infrastructure and President of Rail Transport Office), had no impact on the effectiveness of task implementation within the framework of railways crisis management system. During the biggest breakdown of rail traffic control, the President of Rail Transport Office, the national safety authority and national regulator of rail transport, was not notified by PKP PLK S.A. with advance information regarding the rail lines manager’s deliberate and planned remedies that might have an impact on the disruption of rail traffic on nearly the entire rail network. The Rail Transport Office pointed out that in case of disruptions of train traffic, the infrastructure manager should have taken all necessary steps to restore uninterrupted train traffic. and at the same time, should have notified the Rail Transport Office of the recovery plan. PKP PLK S.A. should have implemented appropriate mechanisms in external communication and crisis management.

4. Diagram – Rail traffic crisis management organisation chart

In NIK’s opinion, the procedures adopted and applied by the railway companies under the leadership of PKP PLK S.A., within the framework of the railway crisis management system, enabled operators to reliably prepare the railway infrastructure, manage railway traffic and ensure the safety of people on railway premises in the event of a crisis situation.

The procedures developed were a grassroots initiative of railway companies. The Minister of Infrastructure, despite being obliged to create a crisis management system on the railway, did not even join the agreement concluded by railway companies in 2017.

The agreement of 2017 was concluded between the following entities: PKP S.A. (railway stations) PKP Informatyka Sp. z o. o. (IT systems & operational security), PKP Telkol sp. z o. o. (radio communication & Radio-Stop system), PKP Energetyka S.A. (energy) with company PKP PLK S.A., as a leader. The agreement concerns the organisation of national rail crisis management system and monitors current operational and transport work on railways managed by PKP PLK S.A. at rail stations and terminals. The railway companies crisis management system was created by specially appointed teams at various management levels to be triggered in the event of threats and crisis situations.

The audit stated that the safety management systems of rail operators implemented by rail carriers enabled the safe operation of rail vehicles and appropriately managed rail infrastructure by regulating a wide range of procedures and rules of conduct in the event of specific events, including those of a crisis nature. However, this system, required by the provisions of the Rail Transport Act, was not an element of crisis management within the Crisis Management Act, but was only its informal supplement.

Audit recommendations

NIK recommended to the Prime Minister first to undertake action within his supervisory authority, which aims to ensure formal participation of the President of the Office of Rail Transport in the railway crisis management system. Secondly, the Prime Minister should undertake legislative initiatives aimed at specifying the substantive scope of crisis management plans of ministers and heads of central offices. NIK stated that the present provisions of laws do not uniformly specify requirements as to the content of crisis management plans developed at various levels of public administration, thus the coherence and complementary of crisis management plans of all public administration are missing.

The NIK recommended the Minister of Infrastructure to develop and implement detailed rules and procedures for the operation of the Statutory Crisis Management System on the railway, taking into account the participation and specifics of activities of all operators within this system, in particular, railway companies and President of the Office of Rail Transport.

Train Hacking Case

NIK’s audit on rail safety crisis management functioning aimed to explain reasons of events and issues connected with rail lines’ crisis management systems functioning. However, the audit did not cover a worth mentioning trains’ hacking case, as disclosed by a company which provided maintenance services for one of rail operators, Koleje Dolnośląskie. In this case, 30 trains were produced by a different Polish company, which, after having an obligatory maintenance, “refused cooperation”, when serviced by the company that won the tender. The company that provided maintenance was different than original train manufacturer, who also applied but was unsuccessful with their bid. Despite being fully operational, these trains did not run, so the maintenance company decided to hire hackers to better understand the reasoning behind the malfunctioning. Suspicions of the original manufacturer’s potential sabotage were exposed when hackers analysed the software of the train control computers. Their findings indicated that the train manufacturer may have deliberately programmed faults that occurred after other companies serviced the trains, or after a certain number of kilometres. These faults would immobilize trains when certain conditions were met, such as when. a train spent more than ten days in a location within specific GPS coordinates, pinpointed to the locations of repair facilities of several different companies that compete with producer for service contracts. The trains’ software was modified to cause false “failures” , thus immobilizing trains. Some experts suggested that the faults may have been the result of deliberate actions by the train manufacturer that had lost tenders for servicing and maintenance due to higher prices. Hence, the suspicion is that the company may have sabotaged the trains in order to regain orders for their maintenance.

The NIK at present does not intend or plan undertaking audit of this trains hacking case. The above information illustrates a case difficult to imagine, anyways worth mentioning.