The Connected Audit: Thinking Ahead to Maximize Impact

Authors: Loren Yager and Martin deAlteriis, Instructors with the Center for Audit Excellence; Hannah Maloney, USAID Office of the Inspector General

The article does not reflect the views of USAID, US OIG, or the U.S. Government.

Introduction

Many auditors have developed considerable experience conducting each stage of an audit, yet those same auditors often lose momentum when it comes to moving from one stage to the next. One reason is that auditors must get the details right to support convincing findings and conclusions; however, that same focus on the details may prevent an auditor from considering how decisions on one stage will impact the next stage of the audit. Consequently, in addition to developing technical skills needed to execute each stage of an audit, auditors should also develop the ability to think ahead to help an audit move smoothly from one stage to the next.

Fortunately, training, tools, and exercises can help teams develop the skills to maintain momentum between stages and ensure that they achieve the greatest impact from every audit. The overall concept is illustrated in Figure 1, where the key stages of an audit are represented as the outer pieces of a puzzle: drafting objectives, establishing criteria, collecting evidence, and developing the message.

The puzzle illustrates how each stage is naturally connected to the next. The great connector is impact, which should be central to any audit.

For example, an audit team should make decisions on objectives with criteria in mind, so that the team will not have to go backwards and rethink the objectives if applicable criteria are not available. Similarly, decisions on criteria should be made with an understanding of the quality and availability of evidence that will be necessary to establish the condition and keep the audit moving forward. Next, while collective evidence should flow into a coherent, logical message, this transition requires a significant change in thinking from the detail-oriented focus of the evidence to the big-picture “so what” of the message. Finally, the message must tie back to the objectives and address the underlying purpose of the audit. A misstep in any stage can affect impact in terms of timing, resource requirements, authority of message, or strength of recommendations. The hit on team morale and motivation also becomes a residual casualty.

It may seem like a tall order to juggle, but the right tools and skills can help teams manage all the transitions in the audit process.

Drafting Objectives with the Criteria in Mind

Looking ahead to the next stages of an audit begins when a team drafts their objectives. While audit objectives do not have to specifically mention criteria, it is an excellent practice for the team to consider criteria that might apply to the situation. It may not be possible for the teams to make final decisions on the criteria at this early stage of an audit, but the planning is greatly advanced when the teams consider the different possibilities and whether those evaluations can be successfully completed.

For example, a team planning an audit on school construction might initially consider numerous criteria ranging from procurement to environmental compliance. This early discussion would alert the team to the need to narrow the criteria under consideration for the team to make progress at the next stage. If the team decides to narrow the focus to monitoring of school construction, the criteria might zero in on project milestones, periodic reporting, and local building standards for an educational environment.

Consider the Evidence Needed for the Criteria

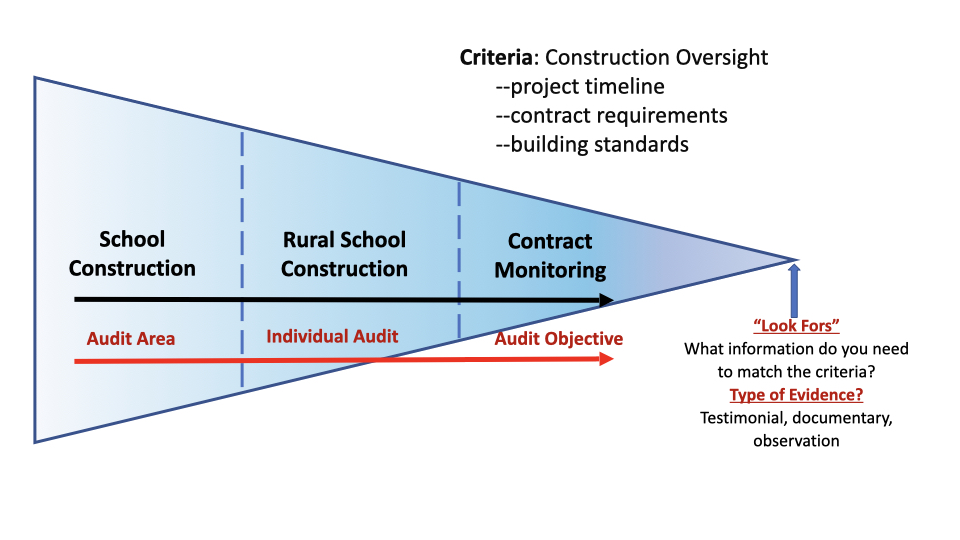

Linking the audit stages becomes even more important as the team refines the criteria that will be applied to an audit objective. Because each evaluative objective necessarily involves a comparison between the criteria and the condition, the evidence that the audit depends on is determined by the choice of criteria. For example, if the team decides to focus on whether the school construction is meeting its deadlines, a key source of criteria would be the timeline for the project. In that audit, the related evidence would be whether the various milestones in the timeline are being met. The school construction would have to meet local building standards and contract requirements as well, so those could also be part of the criteria. As shown in Figure 2, an arrow chart can help teams refine broad criteria as the audit gains focus.

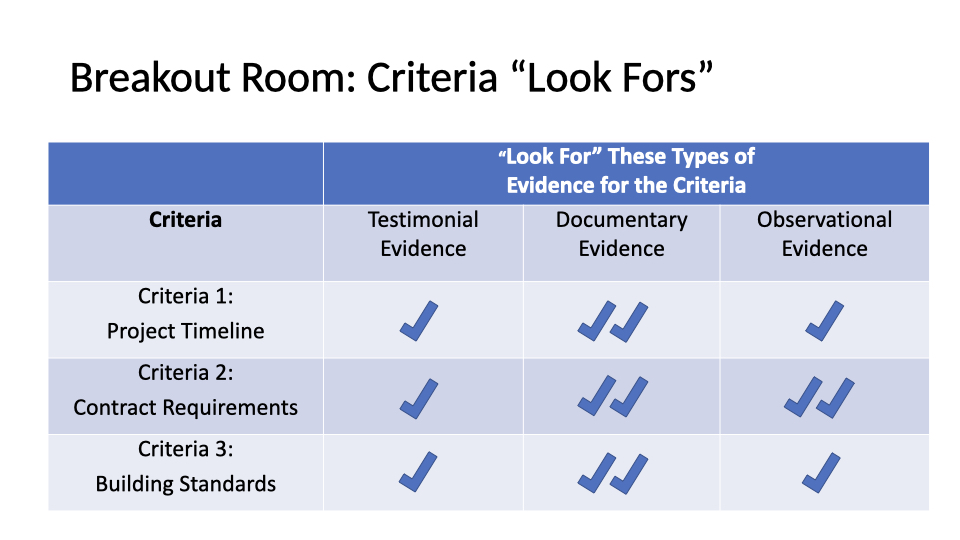

In an evaluative audit like this example, audit teams will benefit from thinking through the evidence that will be required to evaluate against their selected criteria. A useful technique is to identify “Look Fors” using a similar tool as Table 1, tailored for selected criteria.

Table 1 illustrates a first cut at evidentiary “Look Fors” for an evaluative audit of school construction. It shows that the team found documentary evidence to be the best for establishing the condition for the three selected criteria. In addition to a robust meeting of the minds on evidence strength, quality, and availability, this type of table allows the team to confront questions such as whether they will rely on inspections by others, or if the team needs to bring in an expert who is qualified to perform independent observations and inspections as part of the evidence collection.

Further iterations of this table might include more detail about each type of evidence and how it will be collected. For example, the team might create a checklist or data collection instrument for review of the physical inspections to ensure that the team is systematic in its approach. Since evidence collection is costly and most travel and interviews cannot be repeated, these additional planning steps help ensure that the team will collect sufficient and appropriate evidence—not too much, not too little—and not leave it up to chance. A team accustomed to thinking strategically through evidence collection will be better positioned for the next stage of the audit: message development.

Shifting the Mindset from Evidence Collection to Message Development

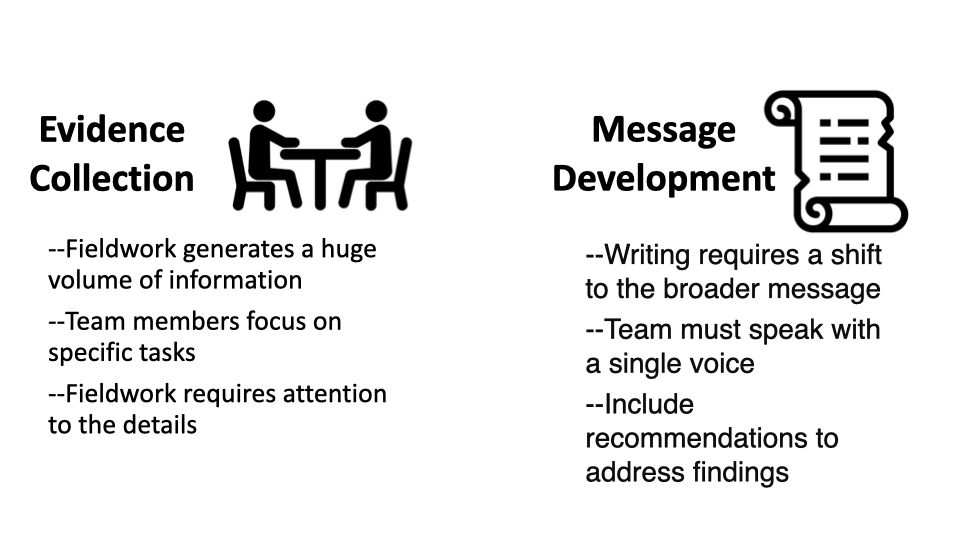

While evidence collection often involves a range of efforts distributed among team members, message development requires a different mindset where team members come together with an overall message for the audit and a clear answer for each objective. As detailed in Figure 3, the tasks involved in evidence collection are detail oriented and often involve team members focusing on specific tasks. In contrast, message development requires those same team members to shift their mindset to the very different task of deciding upon the key findings that will be central to the audit report. The difficult decisions in this stage include deciding how the evidence that was so painstakingly collected should be summarized, reorganized, or in some cases, entirely omitted.

A number of techniques can be used to help with this change in mindset, and all require the team members to confront difficult decisions about the most important issues that the team wants to include in the report. One of the best methods is to create a report outline with message-based headers that signal the key findings for each of the objectives. An overall title for the audit report similarly indicates the tone and direction of the work that follows. Even if the title and headers are changed during the editing process, the outline creates a jump start on the transition between evidence collection and report writing. An outline with simple subject-based headers does not serve the same purpose since it allows the team to delay making those tough decisions.

Other tools that can be used include various templates that require the team to provide the criteria, condition, cause, and effect (CCCE), or a record of audit finding (RAF), which includes those elements along with key findings and examples. These templates can be used in conjunction with a practice called ‘writing on walls’ where team members are able to display and organize all of the evidence in a series of sessions rather than sending written materials back and forth. Whichever tools or techniques are used, the essence is that team members cannot avoid making decisions about the big picture message if they want to successfully navigate the transition from evidence collection to message development and report writing.

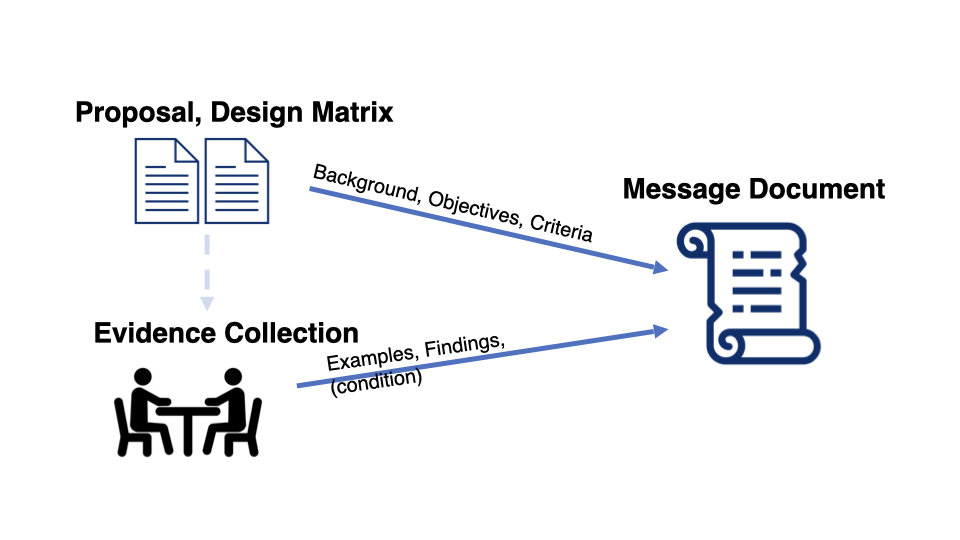

The good news is that much of the remainder of the audit material should be available from the earlier stages of the audit, including the background, objectives, and criteria, as illustrated in Figure 4. Access to this material greatly helps in compiling the message document but can also become a distraction if the team spends too much time fine-tuning those sections and avoids the decisions needed regarding the key findings.

Achieving Impact Through Recommendations

Although audit organizations have numerous ways to achieve a positive impact, including actionable recommendations is the most direct way to translate audit findings into impact. At this point in the audit, the team should have all the necessary elements to craft recommendations, including sufficient evidence to support the findings. The team should continue the process of thinking ahead by looking to the desired corrective actions of the audited entity. This requires the team to understand the cause of the findings, which can sometimes not receive due care when the team is focused on collecting evidence to establish condition. One reason is that the cause is often discovered and clarified through interviews rather than documentary evidence, and discussions of the cause can only take place after the condition is known.

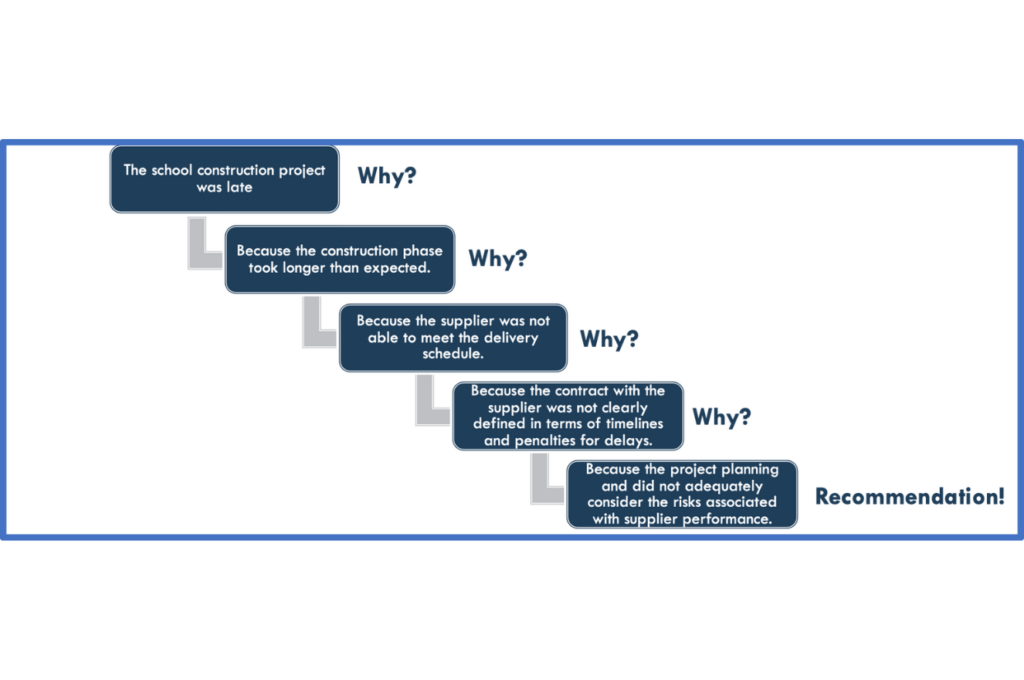

Understanding the cause is essential because recommendations and agency actions are most effective if they address the root cause—rather than just the symptoms—of the finding. There are numerous techniques that can be used to get to the root cause, but one of the simplest is to apply the “5 Whys” shown in Figure 5. This technique is a useful reminder that the root cause may be more fundamental than the first or second explanation, as the initial statements of the cause can look like restatements of the findings. By repeatedly asking why, the team can the team can craft recommendations that address the root cause so the agency actions resolve the fundamental issue—and maximize the impact of the audit.

Conclusion

An impactful audit report is more than a collection of elements; it requires a connected audit process that ensures smooth transitions between stages and maximizes the potential for positive change in the audited entity. By drafting objectives with criteria in mind, considering the evidence needed for each criterion, and shifting the mindset from evidence collection to message development, audit teams have all the elements needed to write recommendations that address the root cause of the finding. These recommendations direct the agency’s attention to the fundamental problem and help ensure that future audits will not repeat the same findings. Moreover, sustained momentum and smooth transitions between stages can help audit teams avoid roadblocks that delay audits, reduce relevance, and affect team morale. The connected audit helps ensure the impact of each individual audit and maximizes the impact of the audit organization as a whole.