Materiality: At the Heart of Auditing

by Åse Kristin Hemsen, Stig Kilvik and Mona Paulsrud, Office of the Auditor General, Norway

Why should Supreme Audit Institutions (SAIs) report matters to their legislatures? Why some issues but not others? For whom are these issues important?

These questions trouble SAIs globally—in daily operations, as well as in audit prioritization. Yet, literature and discussions addressing these questions are scarce.

“Materiality is relevant in all audits. A matter can be judged material if knowledge of it would be likely to influence the decisions of the intended users. Determining materiality is a matter of professional judgment and depends on the auditor’s interpretation of the users’ needs. This judgment may relate to an individual item or to a group of items taken together.

Materiality is often considered in terms of value, but it also has other quantitative, as well as qualitative, aspects. The inherent characteristics of an item or group of items may render a matter material by its very nature. A matter may also be material because of the context in which it occurs.”—International Standards of Supreme Audit Institutions (ISSAI) 100.

The concept of materiality is well-developed for financial auditing, including a substantial amount of research literature. However, materiality, as defined in ISSAI 100, has not been given equal attention when it comes to compliance and performance auditing.

This article stems from a thesis submitted to the Norwegian School of Economics and concentrates on the subject of materiality when SAIs, having discretion to choose which audits to present, initialize and report compliance and performance audits. The thesis is based on theoretical discussions of ISSAI 100, its definition of materiality, and an empirical study of materiality considerations (as executed by SAI Norway).

THE ISSUES

What should be the overall perspectives on the concept of materiality in public sector auditing given the role of SAIs in a democratic government system?

A cross-disciplinary perspective is necessary to assess the concept of materiality in public sector auditing, and the approach in this article draws upon relevant theories from auditing, economy, law and political science, as well as discussions from:

- Economic welfare theory;

- Research on accountability (within law);

- Theory of democracy as outlined in political science and philosophy; and

- The notion of principal and agent, which explains the relationship between user and auditor.

- The user (principal) is the point of departure.

One specific feature of materiality (as defined in ISSAI 100) is that what is material is a “matter,” which can be information that is both negative and positive depending on user decisions. This aspect differs fundamentally from materiality as expressed in financial auditing, where only “a misstatement” may be considered material by the audit user.

What are specific user needs that form the basis for materiality in public sector auditing?

Specific user needs associated with public sector auditing are related to primary legislative functions of granting public funds, passing laws and exercising control.

Justifying SAIs as institutions is, largely, related to the legislative control function; however, user needs may also be connected to public administration learning and development.

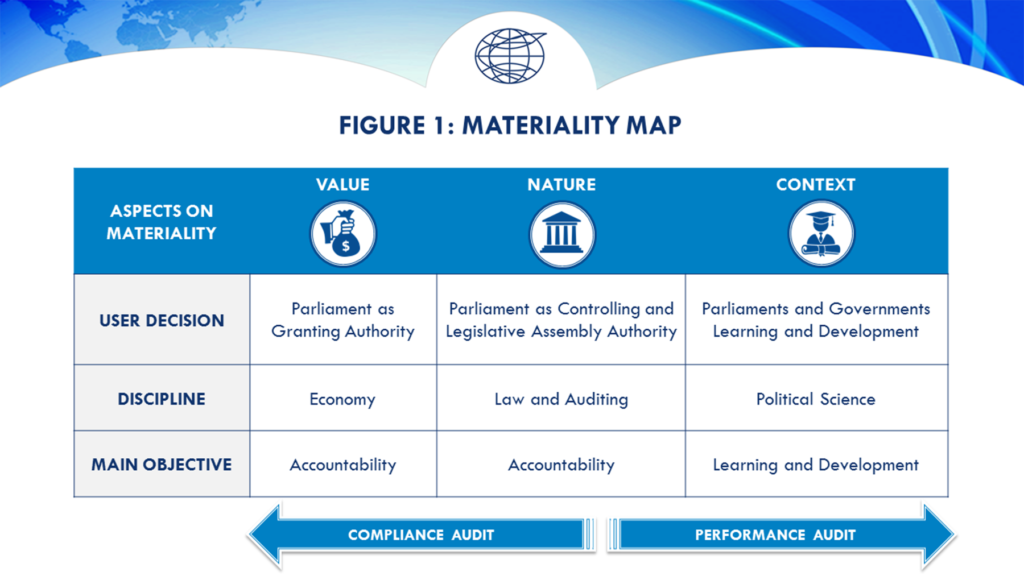

Considering user needs, how are value, nature and context (ISSAI 100) best defined?

In granting public funds, legislative bodies prioritize public resources, and the economic perspective associated with the welfare theory provides the basis to consider the value aspect. Materiality considerations (where accountability and asymmetrical information are at stake) directly link to, and justify, the public control mechanism.

These issues, therefore, should be considered material by their very nature. Context materiality has direct ties to SAI constitutionality—specific legislative statements, as well as the general learning and development of public administration.

Examples of considering materiality by value: (1) Audits initiated and reported due to excessive budgetary spending where government projects considerably exceeded granted parliamentary limits. (2) Matters related to administrative changes covering substantive public spending amounts were reported whether errors were detected (or not) due to materiality factors where economic amounts at stake were considered material by value.

An example of materiality by nature: an audit on how the Ministry of Justice implemented measures to improve public security and ensure preparedness toward thwarting potential future terror attacks. Major deficiencies were reported in an area given specific parliament priority following attacks on government buildings and the Youth Labor party’s political summer camp in July 2011. SAI Norway quelled its level criticism, and parliament precipitated this case’s hearing to emphasize its priority.

“On this matter, a common political consensus that the terror attacks was an attack on democracy was a driver in materiality considerations,” noted one SAI Norway leader.

The most common reason for audits performed and reported across divisions in the SAI of Norway was the ambition of the audit to contribute to change, learning and development in the public sector. This kind of materiality consideration falls clearly into the aspect of “context”.

Other aspects of materiality (in the sense of context): The argument that an issue was audited and reported because it was a central issue of a specific policy area, as for instance a major administrative reform. Hence, it was material in the context of this policy area as such. In the case of reform in the Norwegian health system, this materiality consideration was supported explicitly by parliament.

How can materiality guide a SAI in choosing which compliance and performance audits to carry out and eventually report to parliament?

The different aspects of materiality in public sector auditing can be visualized using a materiality map” (see Figure 1: Materiality Map on page 18) depicting the multi-dimensional, cross-disciplinary considerations that require considerable auditor experience.

Materiality considerations imply a SAI must (1) consider the user needs that should be fulfilled by a specific audit and (2) sometimes choose between conflicting needs. The materiality map can illustrate the different paths associated with materiality considerations.

For additional information about this study or to request a more detailed version of this article, contact:

Åse Kristin Hemsen: ase-kristin.hemsen@riksrevisjonen.no;

Stig Kilvik: stig.kilvik@riksrevisjonen.no; and

Mona Paulsrud: mona.paulsrud@riksrevisjonen.no.